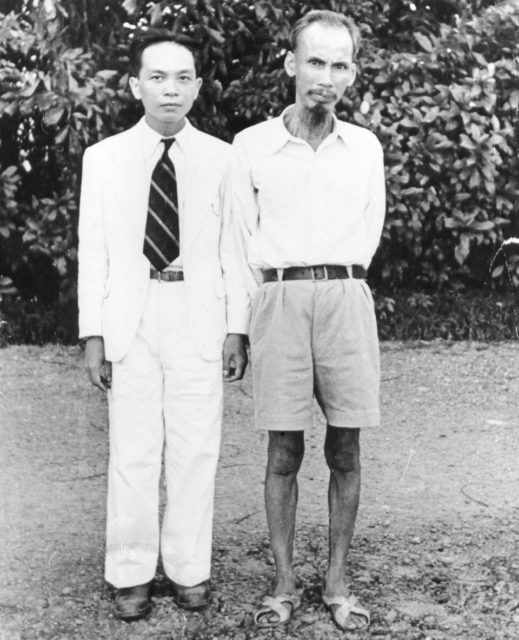

Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap was one of the greatest commanders in the history of warfare. Turning the ragtag revolutionaries of Communist Vietnam into a highly effective army, he took on and defeated two wealthy western powers. A master of tactics, strategy, and supply, he used bicycles and mules to defeat armies equipped with Cold War military technology.

Origins of a Revolutionary

Giap was born in 1912. His father had fought against the French takeover of Vietnam in the 1880s, an event which shaped Giap’s attitude.

During the 1920s, Vietnamese opponents of France split into two groups. Giap aligned himself with the more radical element that included Ho Chi Minh. He was expelled from the French-run National Academy at the age of 15 for taking part in protests. In response, he joined the Communist-led Tan Viet to fight the French oppressors.

Following his arrest during a failed revolt in 1930, Giap took a path of peace, becoming a teacher. He was an active and senior Communist until he was forced into exile in China in 1940. In his absence, his wife died in prison, and the French executed his sister.

Fighting Against Japan

During WWII the Japanese invaded Vietnam. Giap trained guerillas to fight against them. Meanwhile, Ho Chi Minh united the divided Vietnamese resistance under him as the Vietminh.

Fighting Two Enemies

The Vietminh knew that, when the Japanese were driven out, the French, Chinese, and British would step in to dominate Vietnam. To pre-empt this happening, in December 1944, Giap began leading attacks against the French.

Once the Japanese were defeated, Giap joined in the negotiations over Vietnam’s future. It soon became apparent the French would not leave without a fight.

If Vietnam wanted freedom, then there would have to be war.

The Indochina War: 1940s

In November 1946, war broke out in earnest. Giap led the Communist rebels in his first major battle the following year, halting one side of a French pincer movement into the Communist-held North.

It was a difficult war. The French had superior numbers and supplies. Giap learned from his experiences and the example of Mao Tse-tung in China. Instead of forcing battles, he focused on guerilla warfare and winning hearts and minds.

The Indochina War: 1950s

Mao’s success led to a flow of supplies from China to the Vietminh. Giap was finally able to organize and equip units on the same scale as his opponents. In 1950, he launched his first major offensive, capturing a significant French base at Lang Son and its valuable supplies.

Defeats in 1951 and growth in American support for the French added to the pressure. Giap persisted, kept in command by Ho Chi Minh.

Dien Bien Phu

The final decisive action of the war came at Dien Bien Phu between November 1953 and May 1954. The French dropped a large force behind Vietnamese lines. Giap surrounded them, using bicycles and mules to bring artillery onto nearby hilltops. Over months of siege, he picked off parts of the French camp. When the French surrendered on May 7, it was a huge political and psychological victory for the Vietminh.

Peace and Division

The following day, a peace conference involving the great powers began. Cold War politics meant the outcome was never about what the Vietnamese wanted. The French pulled out, and the country was divided in two.

In the North, the Communists ruled. In the South, Ngo Dinh Diem’s regime became virtually fascist. Further conflict was inevitable.

War Creeps In

In the early 1960s, Giap set up an elaborate supply system called the Ho Chi Minh Trail. It brought supplies and troops South to let him successfully pursue a war of unification.

It was a war that developed by slow, creeping steps. As the conflict grew on the border, Diem began locking up opponents in concentration camps. Then Diem was assassinated as Southern Communists began to fight their rulers. In 1963, America sent in its first troops, determined to keep the South from becoming Communist.

Inch by inch, the army Giap commanded was drawn into a war against a superpower.

The Tet Offensive and Khe San

The war slowly escalated. America brought in more troops. Giap brought forces down the trail. America bombed the trail and the North. Vietnamese soldiers and civilians sought safety in tunnels.

1968 saw two of Giap’s boldest actions and greatest failures. The massive Tet Offensive became bogged down, with the Vietnamese incurring heavy casualties. The Siege of Khe San brought its American defenders close to breaking point without quite bringing victory.

Both were costly. Tet, a bigger disaster, ironically helped his cause more, drawing the world’s attention firmly onto the horrors of the war.

1972: Full War and Final Peace

By 1969, support for the war was collapsing in America. The American government was faced with domestic dissent on an enormous scale and were looking for a way out. Negotiations began. It was a long, protracted process taking place in the shadow of the Cold War.

To shift the balance of negotiations, Giap launched yet another large offensive in 1972. His three-pronged attack made significant progress. As his troops advanced, Vietnam became the center of global politics, great powers arguing with each other over his nation’s fate.

In January 1973, an agreement was reached. Vietnam remained divided, but the Americans left. The colonial powers were gone.

Continuing the Struggle

Giap had achieved his lifetime goal of driving the imperialist West out of Vietnam. He handed over command of the armies to his colleague Tien Dung, who went on to conquer South Vietnam and reunite the country.

General Giap continued to have input on Vietnamese politics and warfare. But with the end of the war with America, his career as one of the world’s great commanders was completed.

Giap died peacefully in 2013 at the age of 102.

Source:

David Rooney (1999), Military Mavericks: Extraordinary Men of Battle.

This article was first published in warhistoryonline.com