It was the closest thing to an apocalypse in 2 million years.

The eruption of the Mount Toba supervolcano some 74,000 years ago, which choked the planet in a volcanic winter for up to a decade – very nearly wiping out humankind in the shadow of its dust.

Or so we thought.

New evidence buried under African soil almost 9,000 kilometres (about 5,600 miles) away from the scene of this colossal explosion reveals a different story – one in which Toba threw its deadly tantrum, but somehow, humans survived and even thrived in the dark wake of the super-eruption.

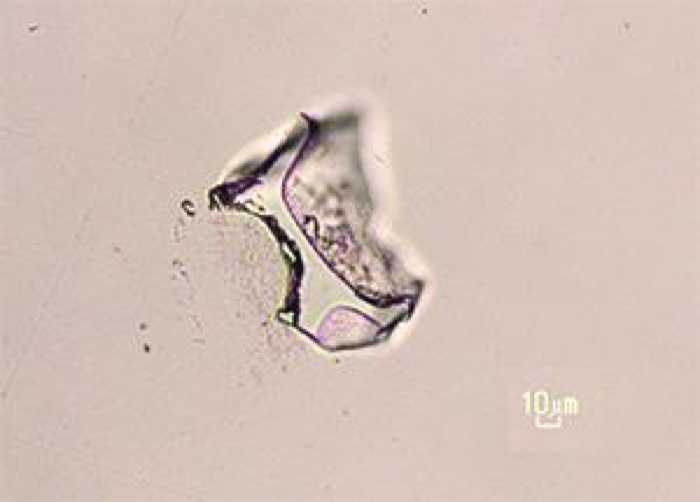

When the Indonesian supervolcano blew its top, covering some 2,800 cubic kilometres(670 cubic miles) of the surrounding area in volcanic ash, it spewed other, almost invisible innards even further: cryptotephra (microscopic fragments of glass) pumped into the atmosphere, which drift endlessly on the wind before falling to the surface.

Under a microscope, almost 75,000 years later, one such glinting piece caught the eye of geoarchaeologist Panagiotis Karkanas from the American School of Classical Studies in Greece, as he was sifting through sediment taken from an archaeological site called Pinnacle Point 5–6, located along the south coast of South Africa.

"It was one shard particle out of millions of other mineral particles that I was investigating," says Karkanas.

"But it was there, and it couldn't be anything else."

Subsequent analysis of the chemical signature of the shard – and of another fragment, uncovered 9 kilometres away – confirmed they both dated from the super-eruption.

But that's not all the team found.

As the team dug, painstakingly analysing each centimetre of a 1.5-metre (5 ft) vertical column of rock layer, they also uncovered stone artefacts, bone, and other cultural remains of the ancient African inhabitants of the land.

Amazingly, the archaeological record suggests that Toba's epic outburst did not disrupt these people's lives, at least to the extent we can discern from their long-ago traces left in the ground.

"These models tell us a lot about how people lived at the site and how their activities changed through time," explains one of the researchers Erich Fisher from Arizona State University.

"What we found was that during and after the time of the Toba eruption, people lived at the site continuously, and there was no evidence that it impacted their daily lives."

If anything, evidence of human activity in the area actually increased after the super-eruption, starkly contrasting with previous research finding Toba's volcanic winter took humanity to the brink of extinction, with years of ash-filled skies taking away our ancestors' sunlight, vegetation, and – ultimately – life.

But with everything we know – or think we know – about the devastating fallout of super-eruptions, how was this uninterrupted survival, let alone thriving, possible?

It's only speculation, but the team thinks that life is better on the coast – not just generally, but in terms of ancient apocalypse survival techniques.

The samples they've uncovered – notably, the first ever showing Toba's impact on human populations – are from coastal areas.

As such, the researchers suggest that maybe coastal living, with its proximity to the ocean and the marine life it contains, could have been what got these ancient humans through the darkness of a deadly volcanic winter.

Elsewhere, divided from the sea, other communities – even ones 9,000 kilometres (or more) distant from Toba – may not have been quite so lucky.

Of course, that's only a hypothesis for now, and not one that everybody agrees with, but future research may well help uncover what really happened when Toba lost its temper so long ago.

Thanks to some of the new analytical techniques refined by the researchers here, it probably won't be too long before cryptotephra from land-locked archaeological locations reveals exactly what happened to people living further from the sea – and then we'll discover just how terrible Toba's wrath really was.

"This is a Holy Grail moment in geochronology," one of the team, archaeologist Curtis W. Marean from Arizona State University told The Atlantic.

"It's so, so rare for us to be able to speak about things at that temporal resolution."

The findings are reported in Nature.