Ayam Brand products are a staple in kitchens throughout Southeast Asia, but few of the people who grew up being nourished by the contents of the company’s colourful cans bearing a proud red rooster will be aware of its connections to France.

One in every two homes in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei has Ayam products in its kitchen at any given time, according to Denis Group, the family-run enterprise that took over the Singaporean company in 1954.

And the home cooks who rely on the company’s affordable foodstuffs have a Frenchman named Alfred Clouet to thank for all those canned sardines, tuna, mackerel, baked beans, coconut milk and so much more.

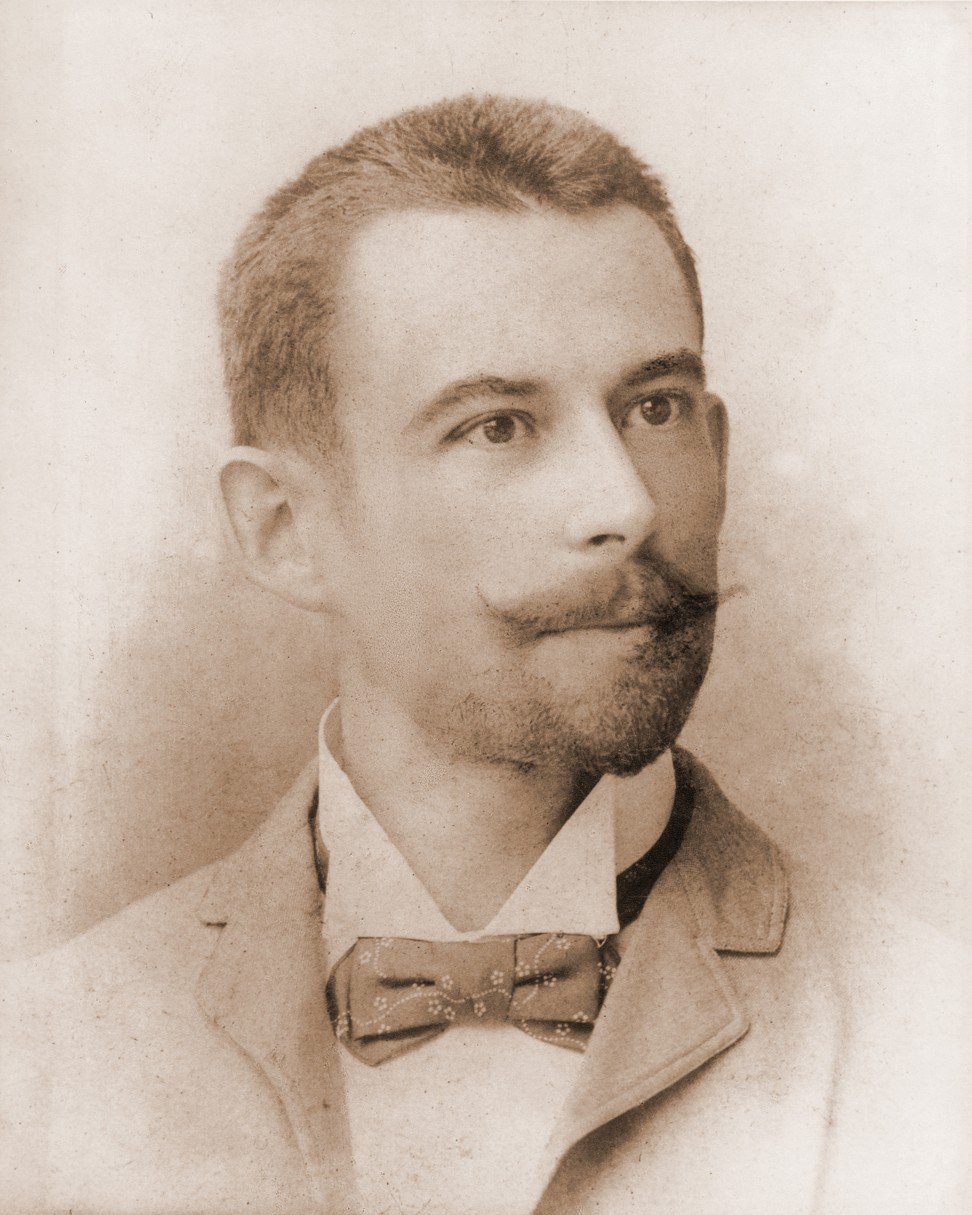

Little was known about the history of Ayam Brand, the current name of a company originally founded in Singapore in 1892, or the life of Clouet, thought to have served as an army officer, until his story was uncovered by historians Danièle Weiler and Jean Bourienne as they studied the history of the French in Singapore.

Clouet was born in 1866 in the northern French port of Le Havre, but never actually served in the army, the historians found. He was an adventurer and intrepid entrepreneur.

In 1889, at the age of 23, the son of a tailor left France to join his pregnant future wife in New York. Few details are known about Clouet’s life in the United States, apart from the fact that his wife died while he was there, but records show that he arrived in Singapore in 1891.

Clouet’s first job in Singapore was with a Frenchman surnamed Labarbe, who ran a trading company specialising in cigars. When Labarbe decided to return to France, he left the company in Clouet’s hands.

As Singapore already had a sizeable expatriate community, Clouet decided to focus on importing premium products such as French perfumes and Bordeaux wines, and registered a new import-export firm, A. Clouet & Co, in 1892. Clouet received 3,000 francs in funding from his father, and soon his registered business addresses included locations on Prinsep Street, Malacca Street, Raffles Quay and Wallich Street in downtown Singapore.

However, the sales of wines and perfumes did not meet expectations, so Clouet decided to explore another product that was then considered premium: canned food.

Canned goods were seen as luxury items in Asia in the days before refrigeration, and were generally out of the reach of ordinary people since they were imported. But Clouet wanted to bring them to the masses. He created a logo consisting of his name and a rooster, and started producing tinned sardines in 1899.

Clouet widened his range to include other canned foods such as mushrooms and peas, but the sardines proved particularly popular.

The business took off, partly because of Clouet’s marketing tactics. In 1900 he submitted his canned goods to the Exposition Universelle (Universal Exhibition) in Paris, where they won gold medals alongside other goods such as Campbell’s Soup, and he took out advertisements in newspapers. (There are records of Clouet buying advertising space in Singapore’s Straits Times as early as 1904.)

At that time, the company was still not yet known as Ayam.

“Our brand, in the beginning, was never called Ayam Brand,” Denis Group marketing director Hervé Simon told the South China Morning Post.

“The only images on Alfred Clouet’s cans were his name, pictures of the gold medals won at the Exposition Universelle, and the rooster, which is a symbol of France, a country known for its premium goods.”

Simon says regular customers started referring to the brand as “chop ayam” – “the chicken brand” in the Malay language – and in the years before the second world war broke out, management decided to change the company’s official name to Ayam Brand.

Clouet contributed to the building of modern Singapore in other ways. He imported colourful European tiles, which wealthy Peranakans – ethnic Chinese residents of Indonesia and Malaya – used to decorate their shophouses, some of which can still be found in modern Singapore.

A. Clouet & Co’s tiles also line The Majestic, a painstakingly restored theatre built in 1928 that used to be the epicentre of Singapore’s Cantonese opera scene. When Denis Group took over in 1954, Ayam was a niche brand that focused on Singapore, Malaysia, and Brunei. But under the new management, it expanded to 30 markets around the world, including Australia, New Zealand, France and Britain.

Today, 2,100 people work for Ayam Brand, mainly in Malaysia, where it operates factories in Taiping (since 1975) and Batu Pahat (since 2000). A factory has also operated in Ho Chi Minh City since 2015 and a new one is due to open in Indonesia in the coming year.

Like Ayam Brand itself, the family-owned Denis Group has an interesting history. Etienne Denis, the captain of a trading ship, founded the company in France in 1862. Initially his main market was South America, but sea blockades during the American civil war prevented his ships from sailing to South American ports.

However, the collapse of those trade routes provided a new opportunity for Denis. He had the foresight to predict that the future of global trade would revolve around Asia, and he started sailing a modest schooner brig named La Mouette (The Seagull) to trade with countries in Asia.

Schooner-type vessels were some of the fastest long-range sailing ships of their time, which meant Denis had a chance to transport perishable goods to far-flung regions. He sent his sons to scout the viability of cities such as Bangkok, Hong Kong, Saigon and Singapore as export destinations.

Today, Denis Group is run by Etienne Denis’ fifth generation of descendants and is still 100 per cent owned by the family.

When Denis Group, then known as “Cie Denis Frères” or “The Denis Brothers Company”, acquired Ayam Brand, it had already been many years since Clouet sold his shares in the company and moved to Egypt to become a director on the board of the Suez Canal. He had just divorced his third wife and eventually married an Egyptian woman named Zeinab el-Saqqaff, of Singapore’s prominent Alsagoff family. Clouet died in Cairo in 1949, at the age of 83.

Denis Group has continued to expand Ayam Brand’s portfolio, which now comprises not just canned goods but also Asian cooking ingredients, which are sold in Western markets.

Simon says he has seen Ayam Brand products stocked in every corner of the world – while holidaying in Tasmania once, he even found a small shop on an island stocked full of its cans. With a healthy market share in countries such as Australia, France and New Zealand, Denis Group considers itself something of a global tastemaker.

“For example, we worked hard to introduce canned baked beans to Thai consumers,” Simon explains. “Clouet was quite a genius in the way he brought new products to consumers, such as sardines and tuna in Malaysia and Singapore,” he adds.

Over the decades, the group has been able to withstand many challenges, such as the depreciation of the Malaysian ringgit in 1997, and since 2010 has been committed to protecting the environment by using only palm oil from sustainable sources.

In recent years, conservation group the WWF asked Ayam Brand to help it convince other companies to adopt this practice, and together they created the Southeast Asia Alliance on Sustainable Palm Oil, which lobbies businesses.

The company continues to invest in research and development, so that it can keep up with changing consumer habits. Producing its famous canned sardines – the original product launched by Clouet – is no small task. The company regularly sends quality and procurement workers all over the world in search of supplies of the fish.

“It is difficult to find sardines, because they are constantly migrating,” says Simon. “They might stay in South African waters for a few years, then leave for the east coast of North America.”

Fishing regulations have also been tightened worldwide, and climate change has made sardine migration harder to predict.

Denis Group has also ventured into e-commerce, and in some markets its online sales are as high as 15 per cent of the total. While it automates and digitises processes to make them less labour-intensive and more eco-friendly, some tasks are still completed the same way they were when Clouet founded the company.

“The packing of sardines remains a very manual task,” says Simon. “You can’t automate this process, so our employees still place them into the cans by hand.”

Source : South China Morning Post