Indonesia is a country that has a long and complex history, and one of the most significant periods of that history was the era of Dutch colonialism. For hundreds of years, the Dutch ruled over what was then known as the Dutch East Indies, a vast territory that included much of present-day Indonesia. Despite this long period of Dutch influence, however, there are surprisingly few tangible remnants of that colonial era in Indonesia today.

This raises the question: why is there so little evidence of Dutch influence in Indonesia?

One possible explanation is the sheer scope and scale of the Dutch colonial project in Indonesia. The Dutch East Indies were enormous, covering an area of more than 2 million square miles at their height, and were home to tens of millions of people. As a result, the Dutch colonial power had to rely on local elites and intermediaries to govern the territory, rather than attempting to impose their culture and way of life directly. This meant that there was relatively little direct Dutch influence on the daily lives of most Indonesians.

Another factor that may have contributed to the lack of Dutch influence in Indonesia is the fact that the Dutch were primarily interested in exploiting the natural resources of the region, rather than in building permanent settlements or leaving a lasting cultural legacy. Many of the Dutch colonial buildings and structures that do exist in Indonesia today are primarily functional in nature, such as warehouses, forts, and administrative buildings. There are relatively few examples of Dutch architecture or design that were intended purely for aesthetic purposes.

In addition, the Dutch colonial presence in Indonesia was often characterized by violence and oppression, which may have contributed to a desire among Indonesians to distance themselves from Dutch culture and influence. The Dutch were responsible for a number of atrocities during their time in Indonesia, including the massacres across the archipelago. The memory of these events may have made it difficult for Indonesians to embrace aspects of Dutch culture and society.

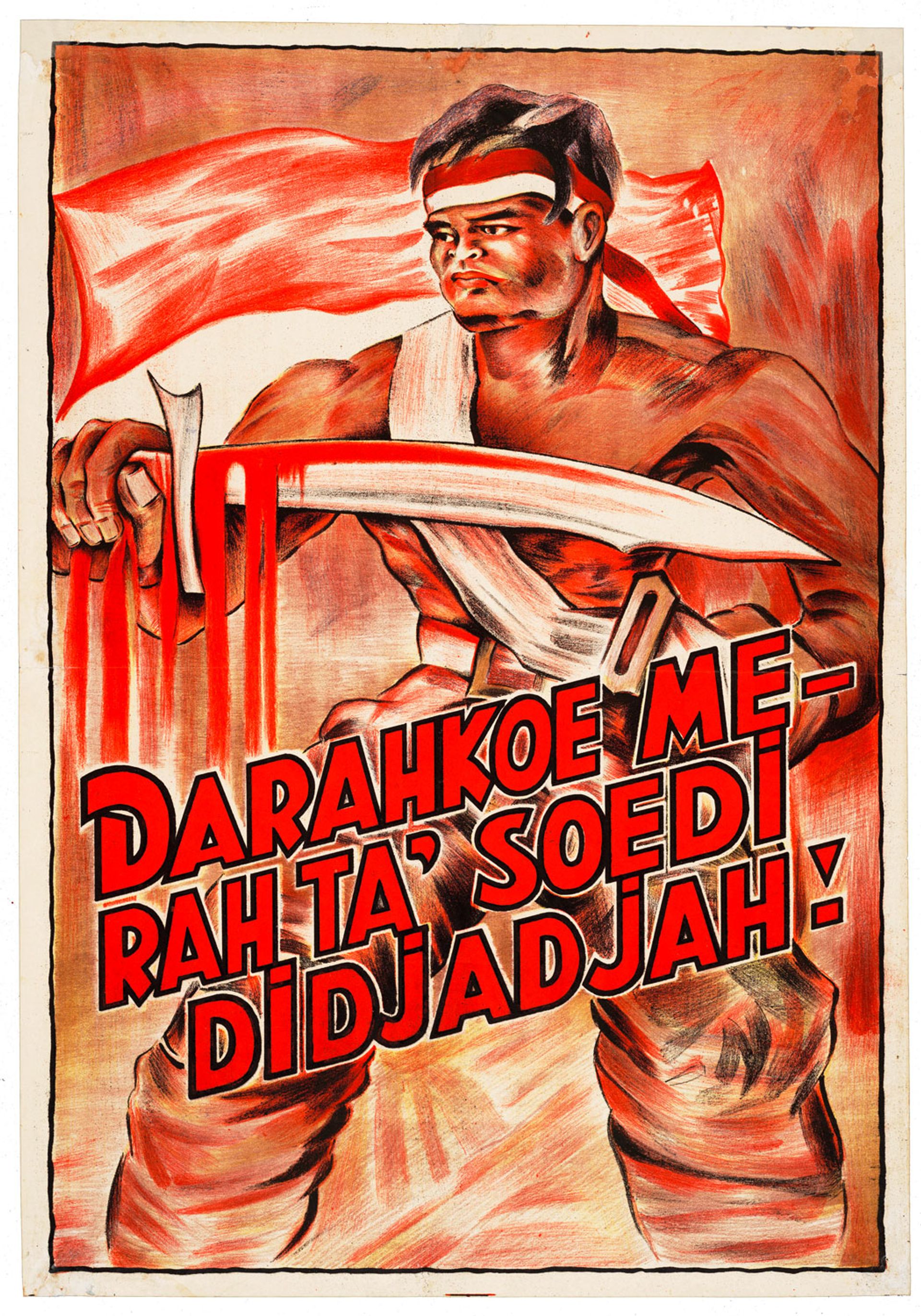

As Indonesians became more educated and politically aware, they began to resist Dutch rule and demand greater autonomy. The Indonesian Nationalist Movement, led by figures like Sukarno and Hatta, gained momentum in the early 20th century and eventually succeeded in securing independence from the Dutch in 1945. As a result of this nationalist sentiment, many aspects of Dutch culture were deliberately suppressed or erased from Indonesian society. Dutch architecture, for example, was seen as a symbol of colonial oppression and was often replaced with traditional Indonesian styles. The Dutch language was also discouraged, and Bahasa Indonesia was promoted as the national language to replace Dutch.

The resistance against Dutch colonialism was not only political and cultural but also violent. Indonesians fought several battles against the Dutch during the colonial period, with the most significant being the Indonesian National Revolution. This was a four-year armed conflict that began in 1945 after the Japanese surrender in World War II, and ended in 1949. Despite the violence and bloodshed, the Indonesian National Revolution was ultimately successful in securing independence for Indonesia. This victory was a testament to the resilience and determination of the Indonesian people, who had endured centuries of colonial rule and were finally able to break free.

Another possible factor is the fact that Indonesia gained its independence from the Dutch relatively recently, in 1945. This means that there has been relatively little time for the Dutch influence to permeate Indonesian society in the same way that, for example, British influence has in India or French influence has in Vietnam. Additionally, the post-independence period in Indonesia was marked by political and economic instability, which may have made it difficult for the country to focus on cultural and artistic pursuits.

Despite these factors, there are still some remnants of Dutch influence in Indonesia today. One of the most prominent examples is the language of Indonesian itself, which is heavily influenced by Dutch. Many words and phrases in Indonesian are borrowed from Dutch, and the language continues to be taught in schools and used in official contexts. Additionally, there are still some Dutch colonial buildings and structures in Indonesia, such as the governor's palace in Jakarta and the Gedung Sate building in Bandung.

Another area where Dutch influence can be seen in Indonesia is in the realm of cuisine. The Dutch brought with them a number of culinary traditions and ingredients that continue to be popular in Indonesia today. Examples include the Dutch-Indonesian dish of nasi goreng, which is essentially fried rice, as well as the use of ingredients like potatoes and cabbage in Indonesian cuisine.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the Dutch colonial period among Indonesians, particularly among younger generations. This has led to a greater appreciation for Dutch colonial architecture and design, as well as a renewed interest in learning the Dutch language. Additionally, there have been efforts to preserve and restore some of the remaining Dutch colonial buildings and structures in Indonesia, in order to showcase their historical and cultural significance.

One example of this is the restoration of the Kota Tua district in Jakarta, which was once the center of Dutch colonial power in Indonesia.

References:

- Ricklefs, M.C. A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1200. 4th ed., Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

- Siegel, J.T. The Rope of God. University of Michigan Press, 2008.

- Arps, B. "The Dutch Colonial House in Indonesia: Architectural Styles and Evidence of Shared Culture." Archipel, vol. 83, 2012, pp. 15-36.

- Harun, H. "The Dutch influence on Indonesian architecture." DW News, 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/the-dutch-influence-on-indonesian-architecture/a-47978791.

- Sudaryanto, A. "The Dynamics of Dutch Language in Indonesia: A Socio-historical Perspective." Journal of Language and Literature, vol. 5, no. 2, 2014, pp. 156-162.

- Oktaviani, R. "Colonial Food Culture and Culinary Nationalism in Indonesia." Indonesian Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2016, pp. 55-72.

- "Restoring the Dutch colonial legacy in Indonesia." Jakarta Post, 15 Mar. 2021, https://www.thejakartapost.com/travel/2021/03/15/restoring-the-dutch-colonial-legacy-in-indonesia.html.