In the heart of Southeast Asia lies an invisible but powerful biological boundary known as the Wallace Line.

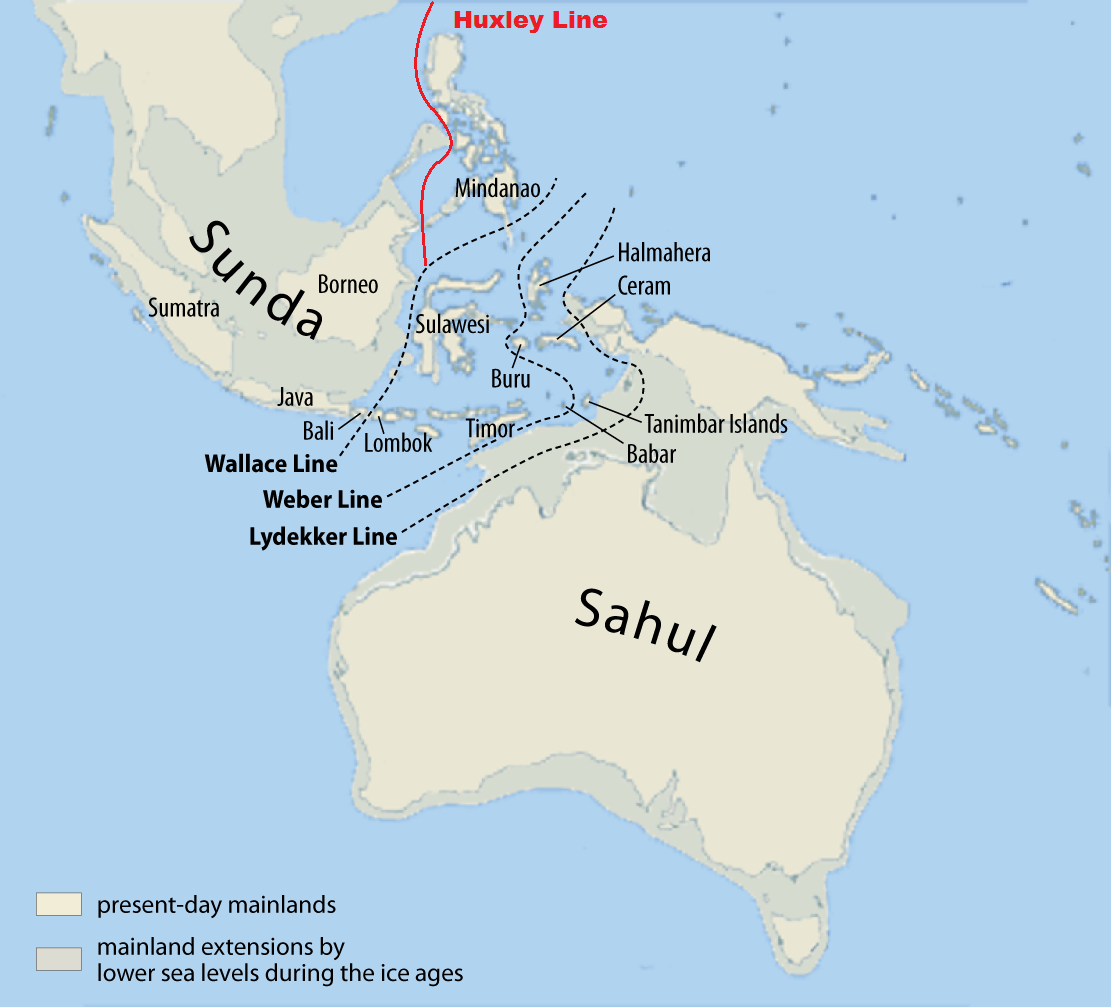

Running between the islands of Borneo and Sulawesi, and between Bali and Lombok, this imaginary line demarcates a striking shift in the animal species found on either side.

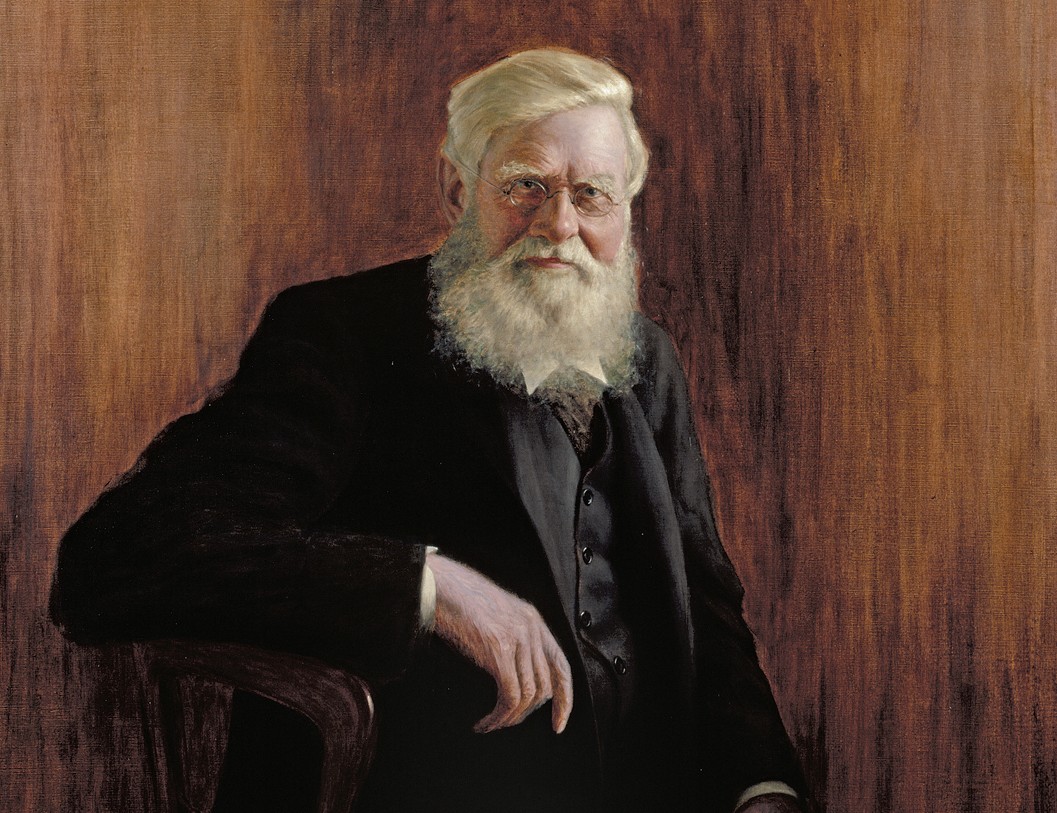

Named after British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, this boundary remains one of the most compelling examples of biogeography, a field that explores the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time.

A Huge Discovery

During the mid-19th century, Alfred Russel Wallace traveled extensively through the Indonesian Archipelago, collecting specimens and documenting the wildlife he encountered.

He noticed something extraordinary: although some islands were separated by only narrow stretches of sea, the animal life on them was dramatically different.

For instance, Borneo and Bali were teeming with Asian species such as tigers, elephants, and rhinoceroses, whereas just across a narrow strait, Sulawesi and Lombok harbored creatures more similar to those found in Australasia, like marsupials and cockatoos.

This observation led Wallace to draw a line through the archipelago, effectively separating the Asian fauna to the west from the Australasian fauna to the east. Despite being so close geographically, these islands were biologically worlds apart.

The discovery not only earned him scientific fame but also reinforced key ideas in evolutionary biology and biogeography, particularly in relation to species distribution and natural selection.

The Geological Underpinnings

The stark contrast in biodiversity across the Wallace Line can be attributed largely to geological history. The islands on either side of the line rest on separate continental shelves.

The Sunda Shelf, to the west, is an extension of the Asian continental plate and was connected to mainland Asia during periods of low sea levels in the Ice Age. This allowed terrestrial animals to migrate freely between the mainland and islands like Borneo, Java, and Bali.

In contrast, the islands east of the Wallace Line, such as Sulawesi, Flores, and Timor, sit on the Sahul Shelf, which is geologically connected to Australia.

These islands have never been connected to the Asian mainland due to the deep waters of the Lombok Strait and other deep oceanic trenches.

These trenches acted as natural barriers that prevented the migration of land animals across the line, resulting in a distinct and isolated evolution of fauna on each side.

A Barrier Rarely Crossed by Life

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Wallace Line is its effectiveness as a biogeographical boundary. Even though Bali and Lombok are only about 35 kilometers apart, the animal species differ drastically.

Elephants, tigers, and other mammals common in Bali are entirely absent in Lombok. Instead, one finds species that are more typically associated with New Guinea and Australia, such as tree kangaroos and marsupials.

Bird species also reflect this divide. Western islands host pheasants and woodpeckers, while the eastern islands are home to parrots and megapodes.

This division is so consistent and striking that it defies the expectations set by such geographical proximity, reinforcing the idea that species distributions are governed as much by geological history as by physical distance.

Modern Implications and Conservation

The Wallace Line remains a vital concept in modern biology and conservation. Scientists studying biodiversity use the line to understand how ecosystems develop and how species migrate and evolve in isolation.

It also underscores the importance of geological events, such as plate tectonics and sea-level changes, in shaping the natural world.

For conservationists, the Wallace Line highlights the importance of preserving both sides of this boundary. The unique biodiversity on either side is irreplaceable, and human activities such as deforestation, mining, and climate change threaten these delicate ecosystems.

Understanding the Wallace Line helps prioritize conservation efforts, particularly in regions that serve as critical habitats for endemic and endangered species.

The Legacy of Alfred Russel Wallace

Although Charles Darwin is more widely known, Wallace’s contributions to evolutionary theory and biogeography are profound. His keen observations and the identification of the Wallace Line have had lasting impacts on science.

Today, the line not only represents a biological boundary but also serves as a testament to the power of detailed fieldwork and scientific curiosity.

In the end, the Wallace Line is more than just an invisible border, it is a symbol of the forces that shape life on Earth.

It reminds us that nature often follows rules not immediately visible to the human eye, and that even narrow straits of water can hold the key to understanding life’s grand patterns.