The repatriation of Eugène Dubois' fossil collection, consisting of more than 28,000 items, from the Netherlands to Indonesia marks a historic moment in cultural recovery. After more than a century abroad, one of the nation's most important scientific legacies has finally returned to its homeland.

But as Indonesia celebrates this long-awaited return, a bigger question looms: When will Britain do the same with the thousands of Javanese treasures looted during the Raffles era?

The Forgotten Looting of Yogyakarta (1812)

In June 1812, under British rule in Java, Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Stamford Raffles oversaw one of the most devastating cultural raids in Southeast Asian history as the Geger Sepehi, or the British assault on the Yogyakarta Palace (Keraton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat).

Tensions had been building since 1811, when the British seized Java from the Dutch, who were then under French control. Raffles initially tried to win over Sultan Hamengkubuwono II, but his authoritarian and dismissive attitude toward Javanese tradition quickly led to conflict.

When the Sultan refused to dissolve his army and submit to British control, Raffles ordered a full-scale invasion. Over 1,200 troops — half of them Indian sepoy soldiers — stormed the palace under the command of Colonel Gillespie. For two days, cannon fire shattered the walls of Yogyakarta. By June 20, 1812, the Keraton had fallen.

After that, it was not governance that took place, but a massive looting. For days, British troops carted away gold, jewelry, gamelan instruments, ancient manuscripts, and royal heirlooms.

Historical records note that every day for nearly a week, five cartloads of plunder left the palace. Four British ships carried the treasures to Europe — two sank at sea, while the other two reached London safely.

What Raffles Took from Java

By the end of his tenure, Raffles had amassed over 2,000 Indonesian artifacts, most of them from Yogyakarta and Central Java. His “collection” included:

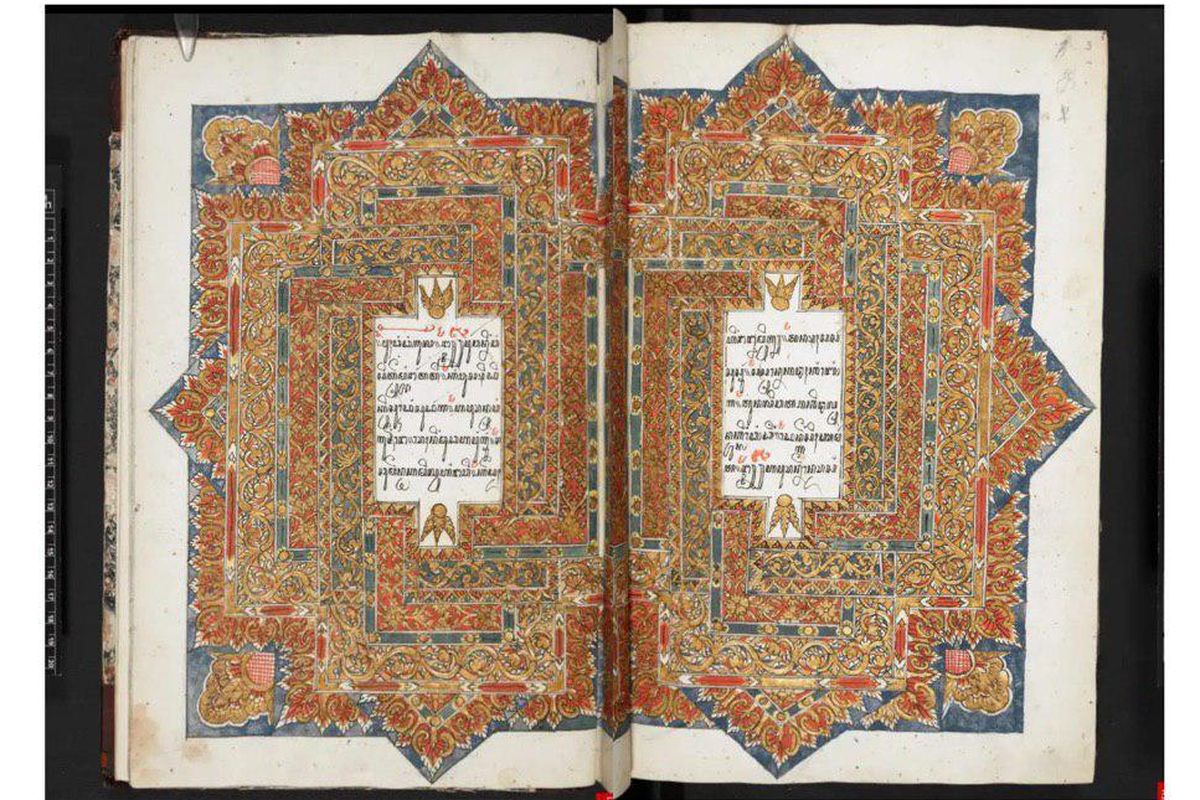

- Around 500 Javanese manuscripts — both on paper and palm leaf (lontar),

- Over 120 metal and stone sculptures,

- 140 items of personal collection, including textiles, coins, jewelry, and theater materials,

- Hundreds of wayang puppets, masks, and musical instruments.

These were later donated to the British Museum and British Library, where they remain today — often labeled as “world heritage collections” without reference to their violent origins.

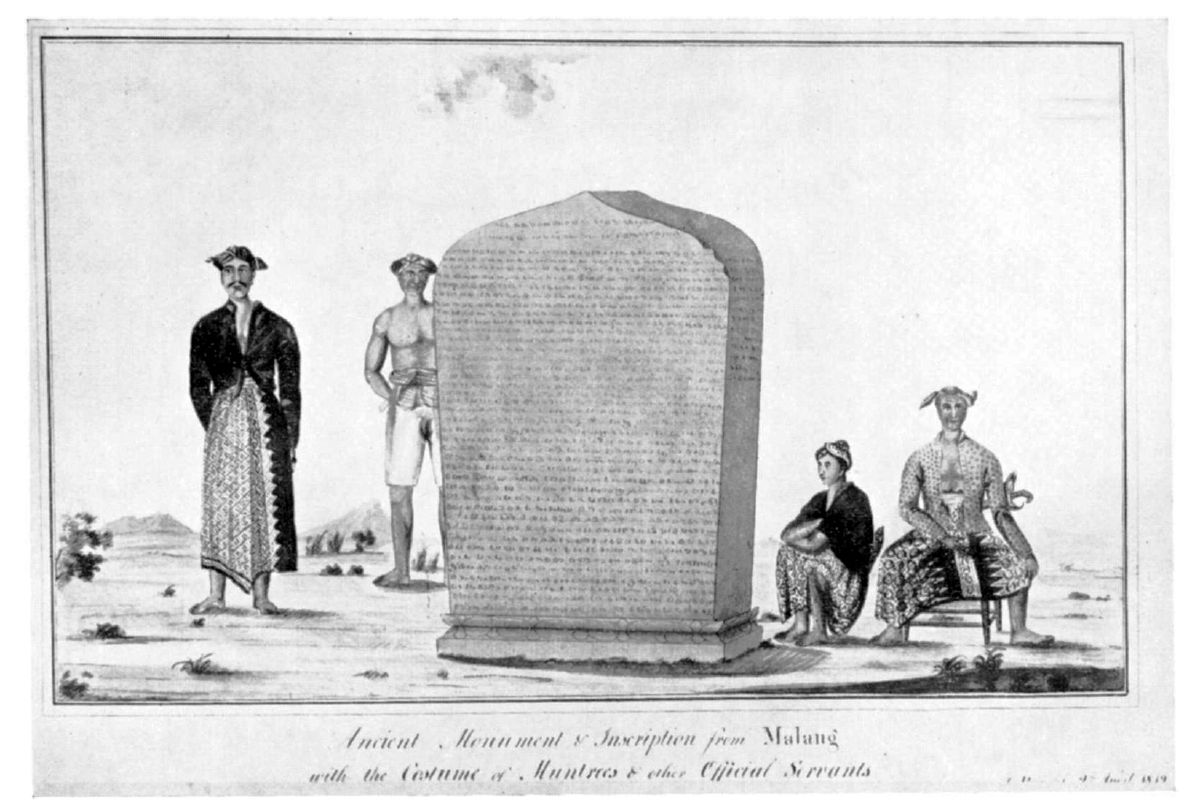

Among Raffles’ most infamous “acquisitions” were two royal inscriptions:

- The Pucangan Inscription (now in India), which chronicles the reign of King Airlangga, one of Java’s most important rulers.

- The Sangguran Inscription (now in Scotland), originating from Mataram Kuno in East Java.

Both inscriptions, along with hundreds of other stolen texts, became the foundation for Raffles’ celebrated book, The History of Java (1817), a work written largely from materials he did not rightfully own.

A Colonial Scholar or a Cultural Thief?

Raffles has long been romanticized in Western narratives as the “founder of modern Singapore” and a “lover of Javanese culture.” But in Indonesia, he is increasingly recognized not as a scholar, but as a colonial plunderer.

According to British historian Tim Hannigan, Raffles’ supposed admiration for Java masked a systematic effort to extract and reframe local knowledge through a colonial lens. His collections were not gathered to preserve Javanese heritage, they were curated to justify British colonial superiority, presenting Java as an “advanced civilization” that the British had “discovered.”

Meanwhile, the Keraton was left stripped of its treasures and archives. Sultan Hamengkubuwono II was deposed and exiled. The looting not only robbed Java of material wealth but also severed the continuity of its historical and cultural memory.

Many Indonesian historians have since described the event as one of the largest acts of cultural theft in Southeast Asian history.

Two Centuries Later: The Call for Repatriation

More than 200 years have passed, and much of Raffles’ collection still sits in British institutions. The British Library holds around 500 Indonesian and Malay manuscripts, including 75 from Yogyakarta, while the British Museum houses hundreds of artifacts labeled “Java Collection.”

In 2019, several of these manuscripts were digitally exhibited in collaboration with the Yogyakarta Palace — but the originals remain in England. Officials from Yogyakarta and Indonesian cultural agencies have repeatedly called for their return, even if only in digital or microfilm form.

Former Indonesian Ambassador to the UK Teuku Mohammad Hamzah Thayeb once noted that the UNESCO 1970 Convention could serve as a legal basis for repatriation — but because these items were taken before 1970, their return depends solely on the “goodwill” of the current holders.

After Dubois, Britain’s Turn?

The recent return of the Dubois fossils from the Netherlands, a collection that had been held for over a century, proves that repatriation is not impossible. It shows that with respect and diplomacy, history can be made right again.

Indonesia now hopes the same courtesy will extend to Britain. Not out of revenge, but out of recognition — that the manuscripts, inscriptions, gamelan sets, and heirlooms taken during the Raffles era are not British heritage, but Indonesian memory.

After all, these objects do not belong in glass cases thousands of miles away. They belong where they were created, in the heart of Java, where their stories began.