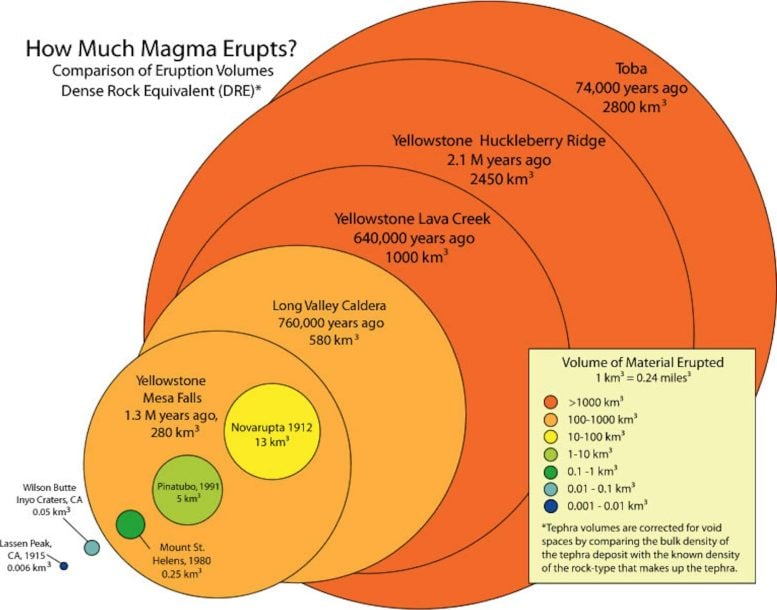

The Toba supereruption happened about 74,000 years ago in what is now Indonesia. It was one of the largest volcanic events in the last few million years. The eruption released about 672 cubic miles or 2,800 cubic kilometers of ash. It created a crater about 62 by 18 miles. Ash rose into the stratosphere and spread across continents. The sky darkened. Sunlight fell. Temperatures likely dropped for years. Near the volcano, acid rain polluted water. Thick ash buried plants and animals. Many life forms close to the eruption probably died. This raises an important question. How did humans survive?

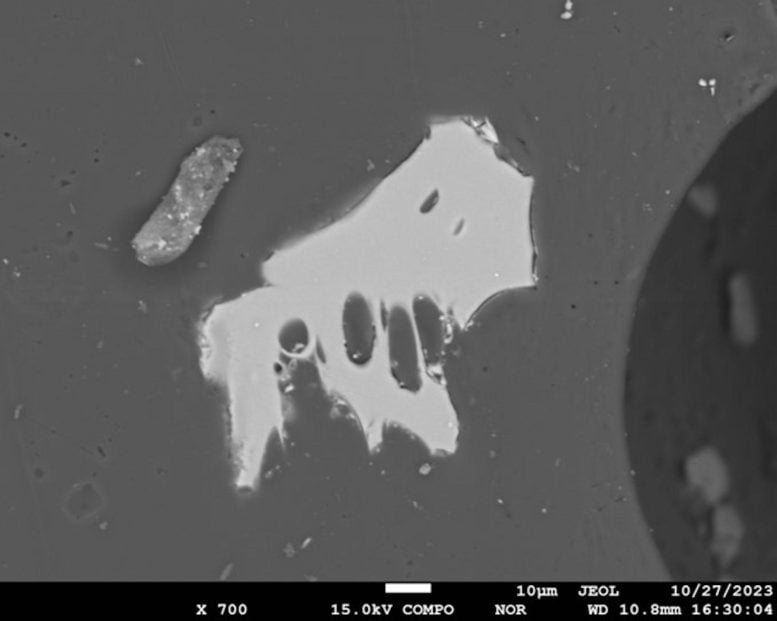

Researchers study volcanic material called tephra to understand past eruptions. Tephra includes visible ash and microscopic volcanic glass known as cryptotephra. Cryptotephra can travel far from the volcano. It is hard to see without equipment. Scientists collect soil samples from archaeological sites. They then isolate the tiny glass grains one by one. Each eruption has its own chemical fingerprint. By studying this chemistry, scientists can confirm whether a grain came from Toba.

Some scientists developed the Toba catastrophe hypothesis. It suggests that the eruption caused global cooling that lasted up to six years. It claims that human populations dropped to fewer than ten thousand people. Genetic evidence shows that modern humans went through a population bottleneck. This means our numbers fell sharply at some point in the past. Whether Toba caused this drop remains debated. Climate data, environmental records and archaeological findings help researchers test this idea.

Archaeologists study sites with traces of human activity such as tools, food remains or fire features. When they find a layer of Toba cryptotephra at a site, they compare what humans did before and after the eruption. People might have changed the stone tools they used. They might have shifted their diet. They might have abandoned a location. These changes help reveal how groups adapted to new conditions.

Evidence from South Africa provides a strong example. At Pinnacle Point 5 to 6, people lived at the site before, during and after the eruption. Their activity increased after the event. They created new tools. They expanded how they used local resources. This shows adaptability rather than collapse. Similar results come from Ethiopia at the site of Shinfa Metema 1. People there faced dry conditions. They moved along seasonal rivers. They fished in shallow pools. Around the time of the eruption they adopted bow and arrow technology. These flexible behaviors helped them survive environmental stress.

Findings from Indonesia, India and China support this pattern. People continued to live in many places that received Toba ash. Human activity did not stop. This challenges the idea that the eruption nearly wiped out humanity. The bottleneck seen in genetics may have come from another event. The story that emerges from archaeology is one of resilience. Humans adjusted. They changed tools. They shifted strategies. They found ways to live through a harsh period.

Studying ancient eruptions helps scientists understand human adaptability. It also guides current hazard planning. Modern programs monitor volcanoes with satellites, sensors and field stations. Examples include work by the US Geological Survey and the Global Volcanism Program. These efforts give communities time to prepare for eruptions. People today have far more knowledge and tools than early humans. Even so, the past shows that adaptability played a key role in survival.

By looking at volcanic deposits, climate data and archaeological evidence, researchers can identify the conditions that supported human resilience. This knowledge helps us plan for future disasters. It also highlights a core human strength. People can adjust to extreme change. The story of Toba demonstrates that creative choices and flexible behavior helped our ancestors face one of the most powerful eruptions on Earth.