Long before the twentieth century, the swastika existed as a positive, widespread symbol across numerous cultures. Its basic geometric form is simple enough to arise independently, yet its meanings were remarkably similar in many parts of the world.

Most often, it represented auspiciousness, well-being, cyclical renewal, or sacred power. The symbol’s global presence highlights the interconnectedness of early human cultures and their shared search for visual expressions of harmony, cosmos, and continuity.

The Origins

The earliest widely accepted evidence of the swastika appears in the Indus Valley Civilization, where it was etched on seals and pottery thousands of years ago.

In the context of early South Asian cultures and later Hindu traditions, the symbol conveyed good fortune, cosmic order, and the divine presence.

It was associated with the sun, prosperity, and the movement of life’s cycles. The swastika continues to be used in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, where it holds deeply spiritual meanings.

In these traditions, the clockwise and counterclockwise orientations can signify different cosmic principles, but both forms are considered sacred.

Its daily presence in religious rituals, festivals, and temple architecture underscores how deeply woven it is into South Asian cultural and spiritual life.

Symbol of Harmony in East Asia

In East Asia, especially in China, Japan, and Korea, the swastika became a significant symbol through the spread of Buddhism.

Known as the wan in Chinese or manji in Japanese, it traditionally marked temples, maps, and artworks to denote auspiciousness, eternity, and the Buddha’s teachings.

Rather than perceived negatively, it remains a benign and widely used icon in these cultures. In Buddhist iconography, it is sometimes depicted on the chest of the Buddha or deities to symbolize the heart of enlightenment.

The symbol also appears in ancient Chinese texts and inscriptions associated with the concept of ten thousand things, a metaphor for the universe and its infinite phenomena.

Its integration into East Asian culture illustrates how a simple geometric form can travel and evolve spiritually without losing its essential meaning.

A Sacred Motif in Indigenous Cultures in the Americas

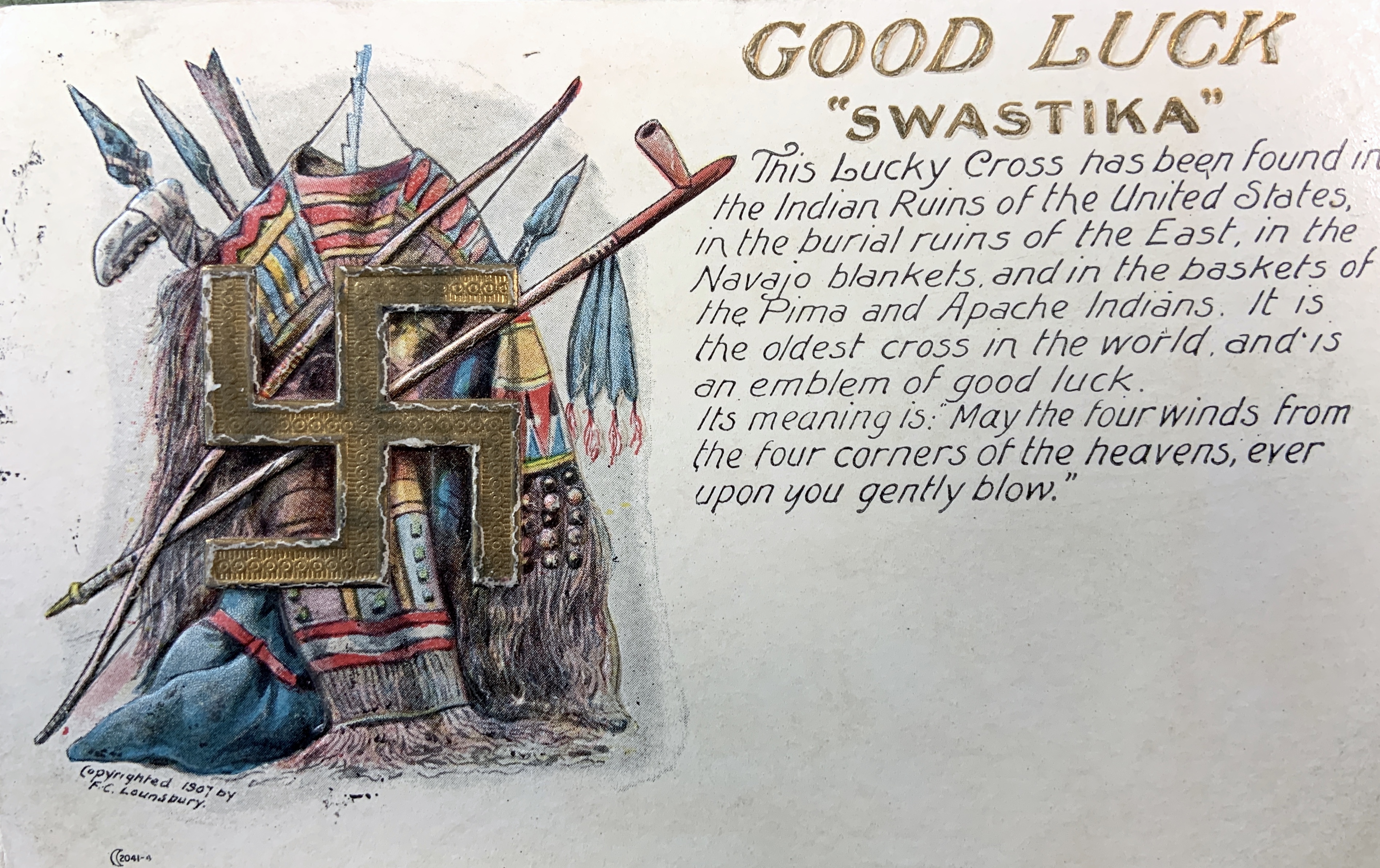

The swastika is not confined to Eurasia. Indigenous cultures in the Americas also created similar symbols long before any contact with Asia or Europe.

Among Indigenous peoples of the American Southwest, for example, the swastika—sometimes described as a whirling log—represented movement, migration narratives, or powerful natural forces such as the wind or the sun.

In Mesoamerican cultures, decorative variations of the swastika appeared in textiles, architecture, and pottery. These symbols often signified continuity, balance, and life energy.

Their independent emergence in the Americas suggests that the swastika may arise naturally when societies attempt to visually express the dynamic interplay of forces in the natural world.

The Swastika in Ancient Europe

Archaeological findings indicate that early Europeans also used the swastika. In Bronze Age Europe, the symbol appears on pottery, jewelry, and weapons.

The ancient Greeks associated it with movement or the rotating sun, while in early Slavic and Baltic cultures it represented fire, the sun, or protective forces.

The symbol appeared in Celtic art and early Germanic artifacts as well. For many European cultures, the swastika served as a charm of good luck, fertility, or protection.

The sheer number of artifacts found across the continent suggests that the swastika was both widely recognized and culturally meaningful.

Shared Geometry Across Different Civilizations

One of the reasons the swastika appears in so many places is its geometric simplicity. A cross with bent arms can easily emerge in different societies that are searching for a way to represent rotation, vitality, or cosmic cycles.

Though these cultures developed independently, many interpreted the shape in similar ways: as a symbol of life, persistence, the sun’s motion, or divine energy.

The swastika’s widespread use serves as a reminder that human beings across time and geography have explored comparable existential questions and found common visual languages to address them.

A Symbol Heavily Overshadowed, but Not Erased

The twentieth-century appropriation of the swastika by the Nazi regime drastically altered its perception in the Western world. Its earlier meanings of good fortune and universal harmony became overshadowed by the horrific ideology and violence with which it became associated.

Yet in many parts of the world, especially in Asia, the symbol continues to retain its ancient significance. Understanding its long global history helps separate the symbol’s original and diverse meanings from its modern distortion.

While the damage to its reputation in the West is profound, recognizing its deeper past provides a fuller, more nuanced picture of how cultures develop symbols and how those symbols can be transformed, misused, or reclaimed over time.