In the highlands of Toraja, South Sulawesi, Indonesia, one of the world’s most magnificent and historically significant funeral ceremonies takes place: Rambu Solo’.

A tradition that has endured since the 9th century, it serves not only as a final farewell but also as a sacred ritual that guides the soul into the spirit realm, honors the ancestors, and strengthens communal solidarity.

A Death Ritual That Cost a Billion-Rupiah

Rambu Solo’ originates from the belief system Aluk Todolo, where “aluk” means belief, “rambu” refers to smoke or light, and “solo’” means to descend—symbolizing a ceremony performed as the sun sets. In practice, this tradition involves a wide range of participants: buffalo and pig farmers, food and beverage suppliers, decorators, equipment renters, hosts, and livestock traders.

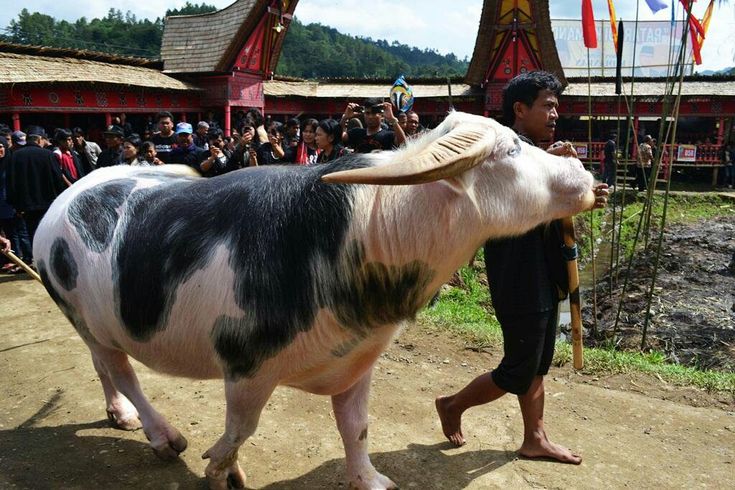

Sacrificial animals play a crucial symbolic role representing family bonds—whether through rara buku (bloodline), pa’uaimata as an expression of compassion, or tangkean suru’, which functions as a reciprocation of past offerings. The patterned buffalo, or tedong bonga, which can be worth hundreds of millions of rupiah, is often the primary sacrificial animal, especially for noble families.

The total cost of holding the ceremony can reach billions of rupiah, particularly among high-ranking nobles whose rites require dozens to more than a hundred buffalo and hundreds of pigs. These immense costs often force families to wait many years before they can carry out Rambu Solo’.

Social Stratification Reflected in the Ceremony

Rambu Solo’ also mirrors Toraja’s social hierarchy, which is divided into several Tana’ strata. The social status of the deceased determines the scale of the ceremony, its duration, and the number of sacrificial animals involved.

Some levels of the ceremony include:

- Didedekan Palungan and Disilli’: for all social classes, especially infants who have not yet grown teeth.

- Dibai Tungga’ and Dibai A’pa’: originally for the slave class but now open to anyone who can afford it.

- Tedong Tungga’: a general-level ceremony with more accessible costs.

- Tedong Tallu/Tallung Bongi: for the middle class up to the nobility.

- Tedong Pitu/Limang Bongi and Tedong Kasera/Pitung Bongi: reserved for high-ranking nobles.

- Rapasan: the highest level, involving the slaughter of a large number of animals.

The four primary categories of these levels are Dasilli’, Dipasangbongi, Dibatang/Digoya Tedong, and Rapasan. However, Rapasan is often chosen for familial reasons despite its extremely high costs. In some cases, the number of buffalo sacrificed can reach 24 to more than 100, in addition to hundreds of pigs.

The Ceremony Process: From Preparation to the Spirit’s Journey

The Rambu Solo’ ceremony unfolds over several days, preceded by family meetings, the construction of ceremonial pavilions, and the collection of sacrificial animals. If the family is not financially ready, the body may be kept for years in the house or tongkonan until preparations are complete. The main processions include:

- Mappassulu’: preparation of the body

- Mangriu’ Batu: transfer of the body

- Ma’popengkaloa: slaughtering of sacrificial animals

- Ma’pasonglo: procession of the deceased

- Mantanu Tedong: buffalo slaughter

- Mappasilaga Tedong: buffalo fighting performance

The procession toward the cliffs where the body is laid to rest reflects the belief that the soul must be guided on its journey to meet the divine. Sacred chants, symbols of nobility, and artistic performances accompany the entire ritual sequence.

Philosophical Meanings and Communal Values

Rambu Solo’ embodies values such as mutual cooperation, solidarity, and adherence to ancestral tradition. It strengthens social networks within Toraja society, especially in the Lembang Lea region. However, it places a significant financial burden on families. Many still carry it out to honor their ancestors, even though not all ceremonies provide direct economic gain.

Historically, Rambu Solo’ also holds unique stories. During the second Dutch aggression, it is believed that Toraja ancestors possessed the ability to make the deceased walk on their own toward the cliffside burial site—a tale that remains part of the community’s cultural narrative.

Regulations on Buffalo Numbers and Customary Practice

Customary rules within Aluk Todolo specify the required number of buffalo to be slaughtered, following a set sequence such as 1, 3, 5, 9, 12, 16, 24, 32, and so on. Only the noble class is permitted to slaughter nine buffalo or more. The number of buffalo serves as a marker of social status, symbolizing philosophical value, material value, and mana’—a concept of authority or spiritual potency.

If a family cannot afford the customary requirements, the traditional leader provides alternatives. Ambe’ Tawang, the Traditional Leader of Lembang Palesan, explains that a family may “knock a plate or bowl for pig feed” as a symbolic gesture. After this, the deceased may be buried first, and once funds become sufficient, a pig can be slaughtered later as a form of respect.

Stages and Performative Arts in Rambu Solo’

High-level ceremonies are typically held in the Rante, a special ceremonial field within the tongkonan complex. The artistic performances showcased are not merely entertainment but also expressions of prayer and reverence.

Early stages include Ma’Tudan Mebalun, Ma’Roto, Ma’Popengkalao Alang, and Ma’Palao/Ma’Pasonglo’, followed by ritual sequences such as Ma’pamula, Tamu Mantarima, Mantunu, and Meaa, or the burial itself.

Despite requiring substantial expense and lengthy preparation, Rambu Solo’ remains a cultural pillar that preserves the ancestral values of the Toraja people. Through this ritual, the community not only honors the departed but also safeguards their identity, solidarity, and social structure. The tradition endures as a legacy that bridges the past with the present generation.