When most people imagine an Asian dragon, they picture the Chinese Long. It is an iconic image of a serpentine creature weaving through the clouds, synonymous with power and good luck. However, the mythology of the dragon extends far beyond the borders of China. Across the Asian continent, different cultures have evolved their own unique interpretations of these divine serpents. Unlike the fire-breathing monsters of Western folklore that hoard gold and demand sacrifice, the dragons of the East are almost universally benevolent, wise, and inextricably linked to the life-giving force of water. They dwell in the clouds to bring rain or inhabit the bottoms of deep rivers and oceans to govern the tides.

The Imperial Standard of China

To understand the variations, one must first look at the archetype. The Chinese dragon is a chimera that possesses the body of a snake, the scales of a carp, the antlers of a deer, and the talons of an eagle. It traditionally lacks wings yet flies through the heavens using mystical power. In Chinese culture, the dragon is the supreme symbol of auspiciousness and imperial authority. Emperors were often referred to as dragons to legitimize their rule. They are cosmic regulators, with the Dragon Kings of the Four Seas believed to govern weather patterns. They do not breathe fire but rather breathe clouds and mist, manipulating the elements to nurture the land.

The Three-Clawed Guardians of Japan

Japanese mythology adapted the dragon, known as Ryu or Tatsu, from Chinese influence, but with distinct changes. While visually similar, Japanese dragons generally have three claws on each foot instead of the four or five found on their mainland counterparts. They are typically associated more closely with the sea than the sky. One of the most prominent figures is Ryujin, the Dragon God who rules the ocean from a magnificent palace made of red and white coral. Ryujin controls the tidal flows with magical tide jewels. Japanese folklore also contains rare instances of malevolent dragons, such as Yamata no Orochi, an eight-headed serpent representing the chaotic forces of nature that had to be tamed.

The Korean Serpent and the Celestial Orb

Korean mythology introduces a unique hierarchy and specific iconography to dragon lore. The full dragon, known as Yong, is a benevolent being related to water and agriculture. A distinguishing feature of the Korean dragon is the Yeouiju, a magical orb often depicted in its claws. This orb grants the dragon omnipotence and the power of creation. Uniquely, Korean legend tells of the Imugi, often described as a lesser dragon or a giant python. The Imugi is a proto-dragon that must practice patience. It lives in water or caves for a thousand years, waiting for the opportunity to catch a celestial jewel falling from the sky. If it succeeds, it transforms into a true dragon, serving as a cultural metaphor for patience and perseverance.

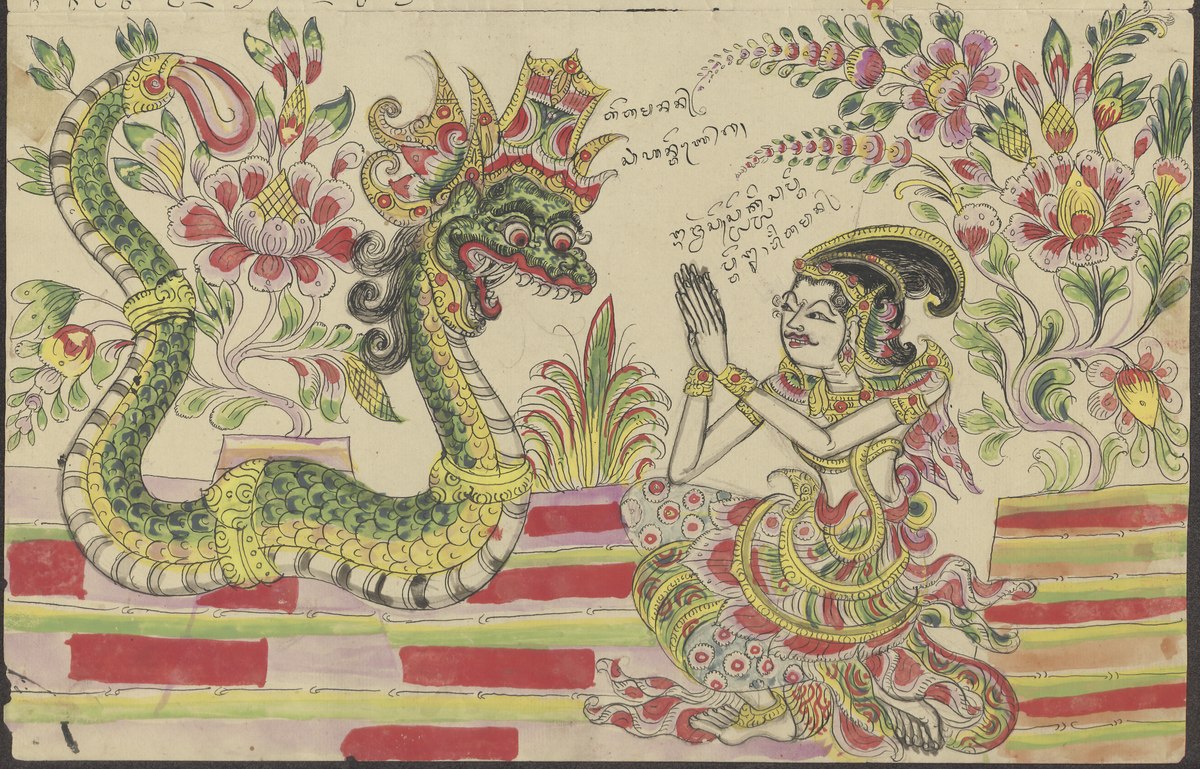

The Nagas of Indonesia

Moving south to India and Southeast Asia, the dragon mythos shifts toward the Naga. These are semi-divine beings that take the form of giant cobras or half-human, half-serpent hybrids. Originating in Hindu and Buddhist cosmology, Nagas act as guardians of wealth and protectors of the faith.

In Indonesia, the Javanese recognize Antaboga, the world serpent who dwells deep within the earth and carries the world on his back. In Bali, the dragon Naga Besukih is a central figure in the origin story of the Bali Strait, representing the volatile connection between the island and volcanic forces.

The Moon Eater of the Philippines

Further north in the Philippines, the dragon takes on a cosmic role in the form of the Bakunawa. Unlike its rain-bringing cousins, this gigantic sea serpent is a moon-eater. Ancient Filipinos believed that eclipses occurred when the Bakunawa attempted to swallow the moon. The people would make loud noises with drums and pots to startle the beast, forcing it to spit the moon back out and return light to the night sky.

Legacy of the Eastern Dragon

The dragons of Asia are as diverse as the cultures that worship them. From the three-clawed sea gods of Japan to the patient serpents of Korea and the underworld guardians of Indonesia, these mythical beings represent more than just folklore. They are symbols of the vitality of nature, the authority of the divine, and the hope for prosperity that unites the region.