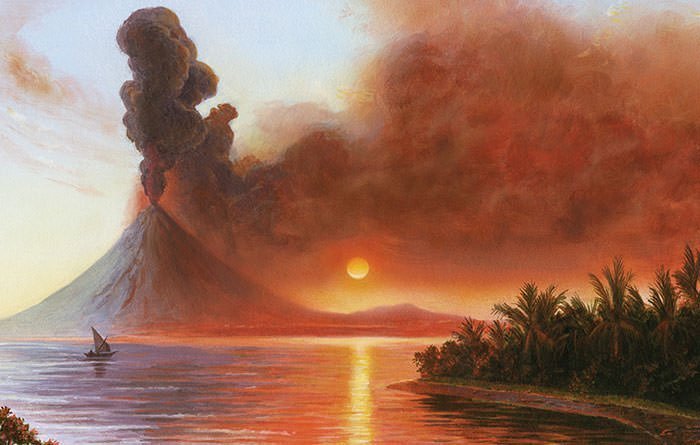

Over two hundred years ago, the greatest eruption in Earth’s recorded history took place. Mount Tambora—located on Sumbawa Island in Indonesia—blew itself up with apocalyptic force in April 1815.

Only few volcanoes had a dramatic and devastating impact as that of Mount Tambora. This volcano produced such a violent eruption that it shielded the Earth from the intense summer sunlight, leading to 1816 becoming “The Year Without a Summer.”

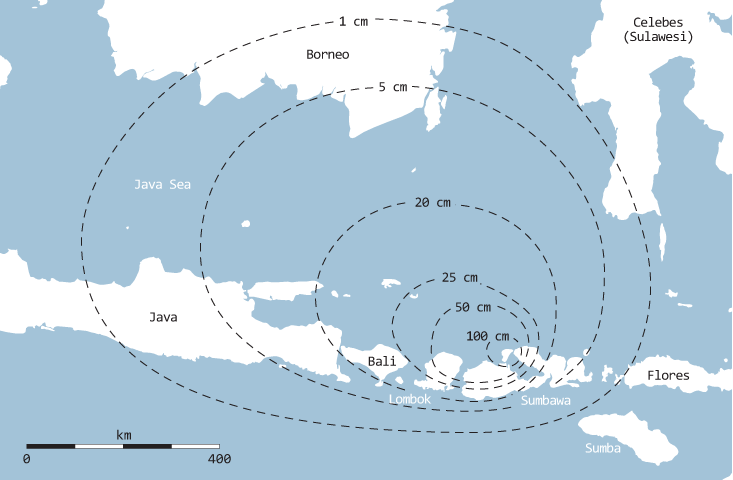

Tambora is located on Sumbawa Island, on the eastern end of the Indonesian archipelago. There had been no signs of volcanic activity there for thousands of years prior to the 1815 eruption. On April 10, the first of a series of eruptions that month sent ash 20 miles into the atmosphere, covering the island with ash to a height of 1.5 meters.

Five days later, Tambora erupted violently once again. This time, so much ash was expelled that the sun was not seen for several days. Flaming hot debris thrown into the surrounding ocean caused explosions of steam. The debris also caused a moderate-sized tsunami. In all, so much rock and ash was thrown out of Tambora that the height of the volcano was reduced from 14,000 to 9,000 feet.

Heavy eruptions of the Tambora volcano in Indonesia are letting up by this day in 1815. The volcano, which began rumbling on April 5, killed almost 100,000 people directly and indirectly. The eruption was the largest ever recorded and its effects were noted throughout the world.

The eruption of Tambora was ten times more powerful than that of Krakatau, which is 900 miles away. But Krakatau is more widely known, partly because it erupted in 1883, after the invention of the telegraph, which spread the news quickly. Word of Tambora traveled no faster than a sailing ship, limiting its notoriety.

The sun-dimming stratospheric aerosols produced by Tambora’s eruption in 1815 spawned the most devastating, sustained period of extreme weather seen on our planet in perhaps thousands of years.

Within weeks, Tambora’s stratospheric ash cloud circled the planet at the equator, from where it embarked on a slow-moving sabotage of the global climate system at all latitudes. Five months after the eruption, in September 1815, meteorological enthusiast Thomas Forster observed strange, spectacular sunsets over Tunbridge Wells near London. “Fair dry day,” he wrote in his weather diary—but “at sunset a fine red blush marked by diverging red and blue bars.”

Artists across Europe took note of the changed atmosphere. William Turner drew vivid red skyscapes that, in their coloristic abstraction, seem like an advertisement for the future of art. Meanwhile, from his studio on Greifswald Harbor in Germany, Caspar David Friedrich painted a sky with a chromic density that—one scientific study has found—corresponds to the “optical aerosol depth” of the colossal volcanic eruption that year.

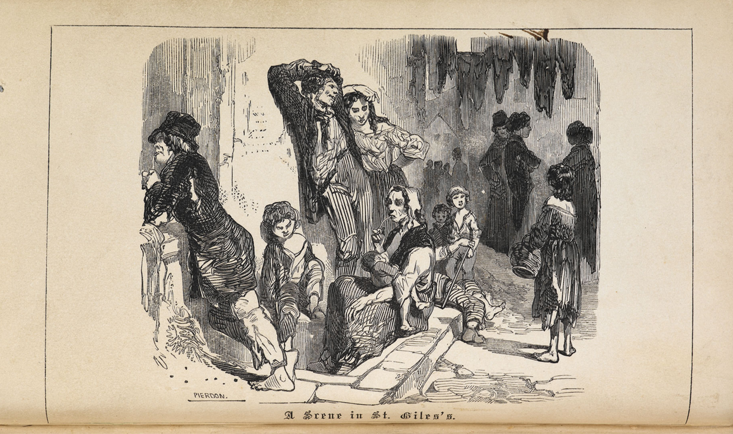

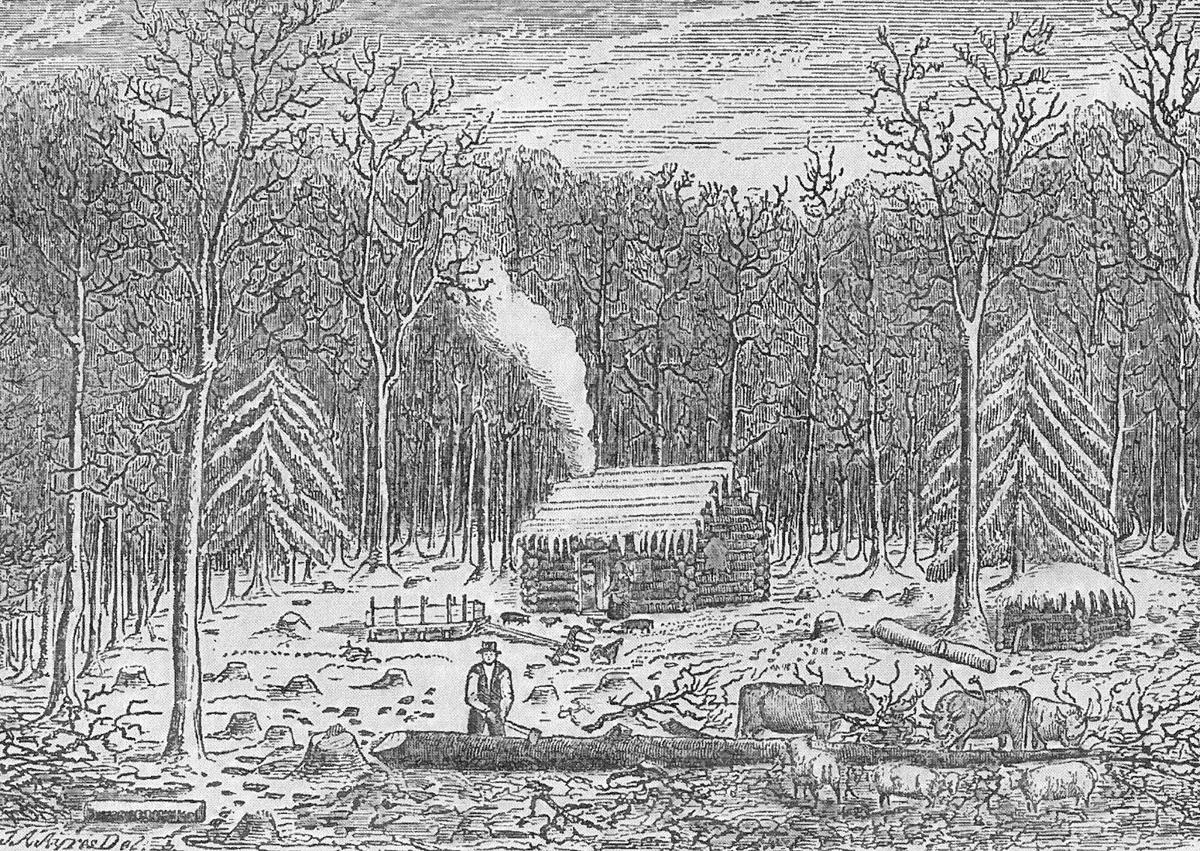

For three years following Tambora’s explosion, to be alive, almost anywhere in the world, meant to be hungry. In New England, 1816 was nicknamed the “Year Without a Summer” or “Eighteen-Hundred-and-Froze-to-Death.” Germans called 1817 the “Year of the Beggar.” Across the globe, harvests perished in frost and drought or were washed away by flooding rains. Villagers in Vermont survived on porcupine and boiled nettles, while the peasants of Yunnan in China sucked on white clay. Summer tourists traveling in France mistook beggars crowding the roads for armies on the march.

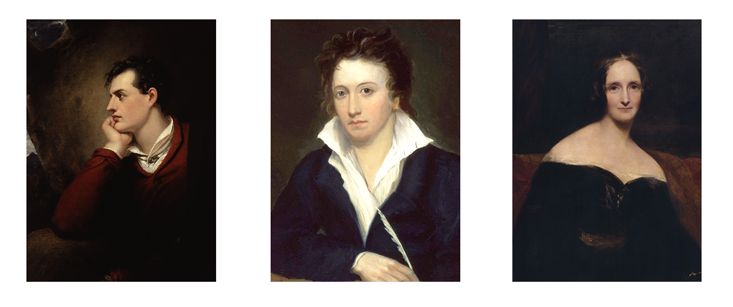

In Switzerland, the damp and dark year of 1816 stimulated Gothic imaginings that still entertain us today. Vacationing near Lake Geneva that summer, Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and his soon-to-be wife, Mary Wollstonecraft, and some friends sat out a June storm reading a collection of German ghost stories.

The mood was captured in Byron’s “Darkness,” a narrative poem set when the “bright sun was extinguish’d” and “Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day.”

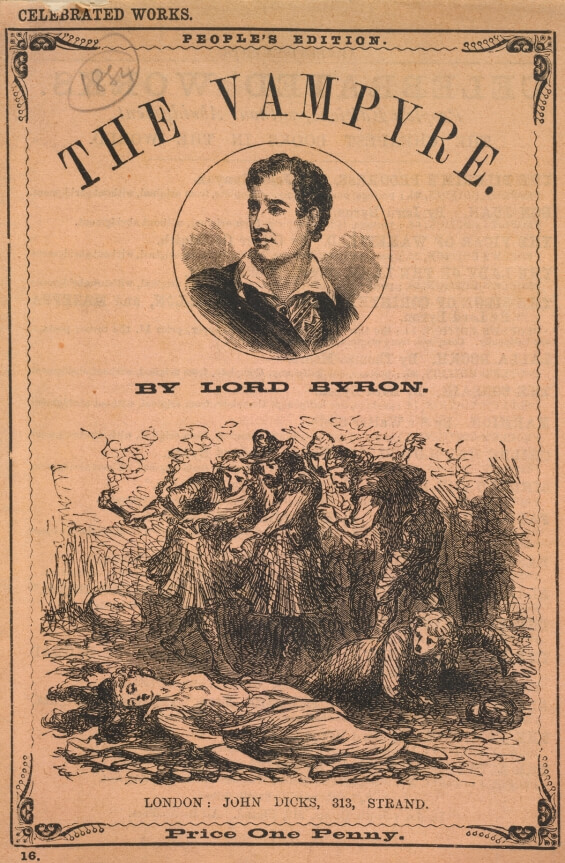

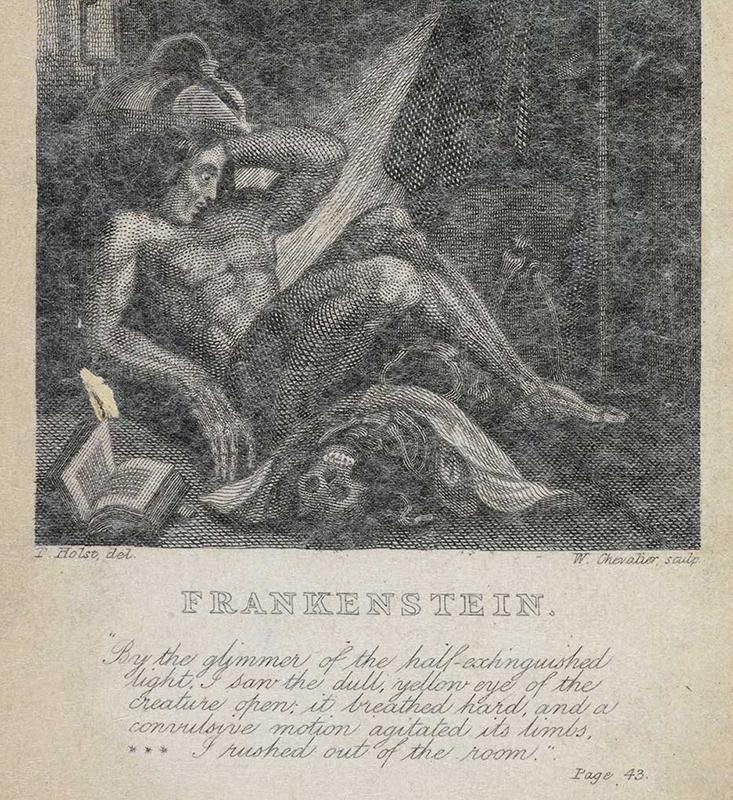

He challenged his companions to write their own macabre stories. John Polidori wrote The Vampyre, and the future Mary Shelley, who would later recall that inspirational season as “cold and rainy,” began work on her novel, Frankenstein, about a well-meaning scientist who creates a nameless monster from body parts and brings it to life by a jolt of laboratory-harnessed lightning.

If we were to experience an eruption like Tambora in modern times, the results would be catastrophic. The global population has dramatically risen by billions of people over the past 200 years, and the consequences of such an eruption occurring in modern times would lead to unimaginable death and devastation. In addition to the eruption itself, simple activities like air travel would grind to a halt as volcanic ash can seize jet engines and cause planes to crash. The global climate change would result in outbreaks of famine and disease practically unseen in modern times.

And maybe, more "monsters" far more frightening are awaiting .

Source and reference: