When COVID-19 hit Indonesia, it devastated industries such as fisheries. However, one sector has gone against the trend: seaweed farming.

A research by The Conversation shows seaweed farming in Indonesia is booming during the pandemic.

There is a range of possible reasons for this change, including environmental conditions, farming practices and the impacts of COVID-19.

The resilience of seaweed farming is important given the nation’s status as the world’s largest producer of hydrocolloid seaweeds. Indonesia produces two-thirds of the global supply. These seaweeds are generally not eaten but are sold to factories for processing into a powder used for thickening foods such as ice-cream.

Research

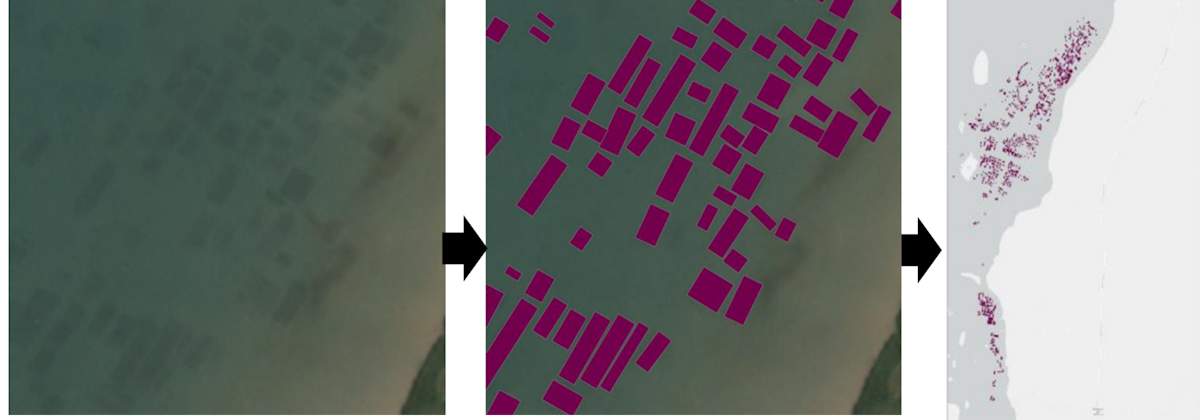

For a case study of the mainland coastline of Pangkep in South Sulawesi, we used newly available high-resolution, high-frequency satellite imagery from US-based Earth-imaging firm PlanetLabs to map seaweed farming over time.

Although Pangkep is just one regency contributing to Indonesia’s seaweed industry, our methodology provides insights into the impact of COVID-19. This approach could be expanded to explore a larger area.

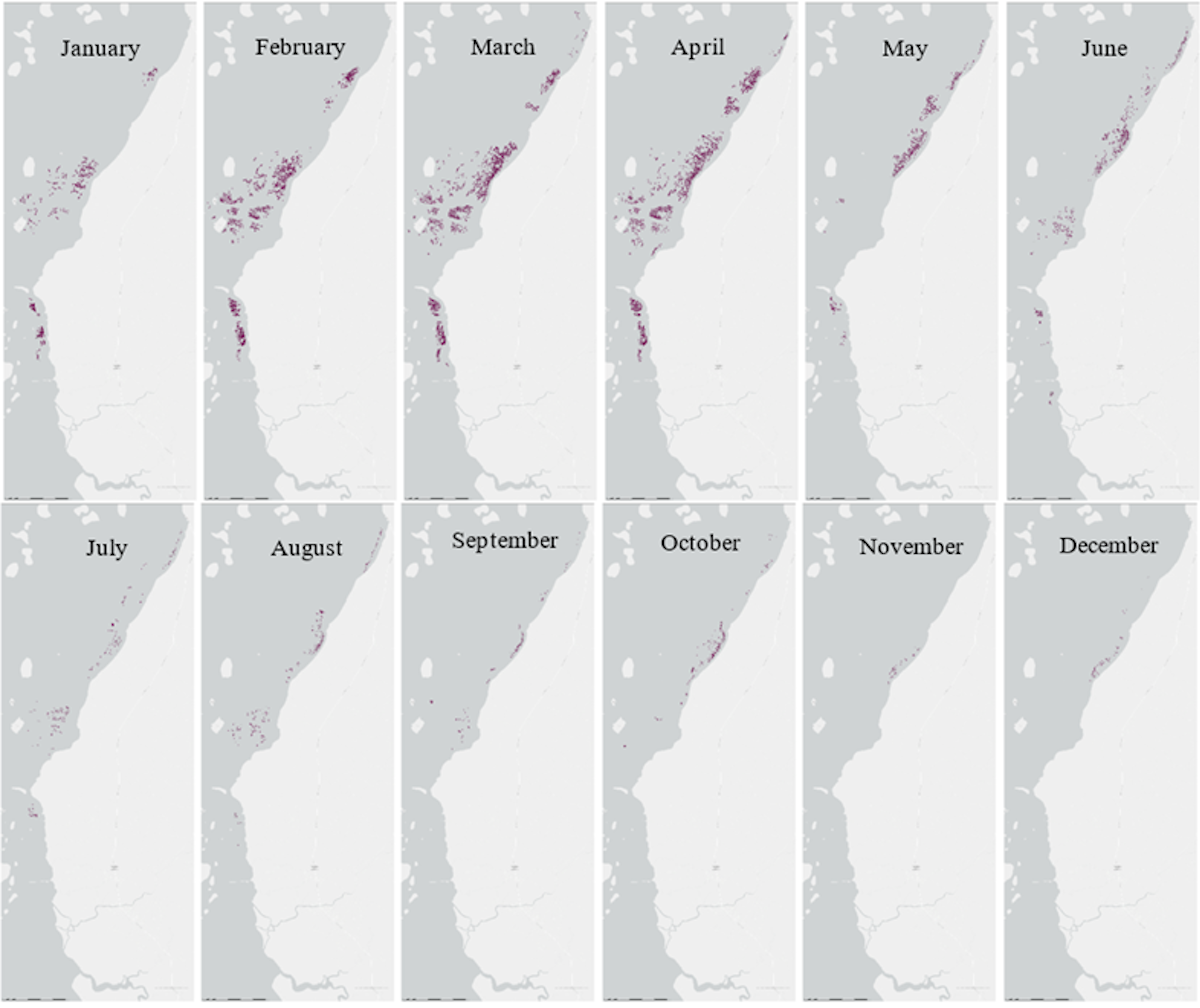

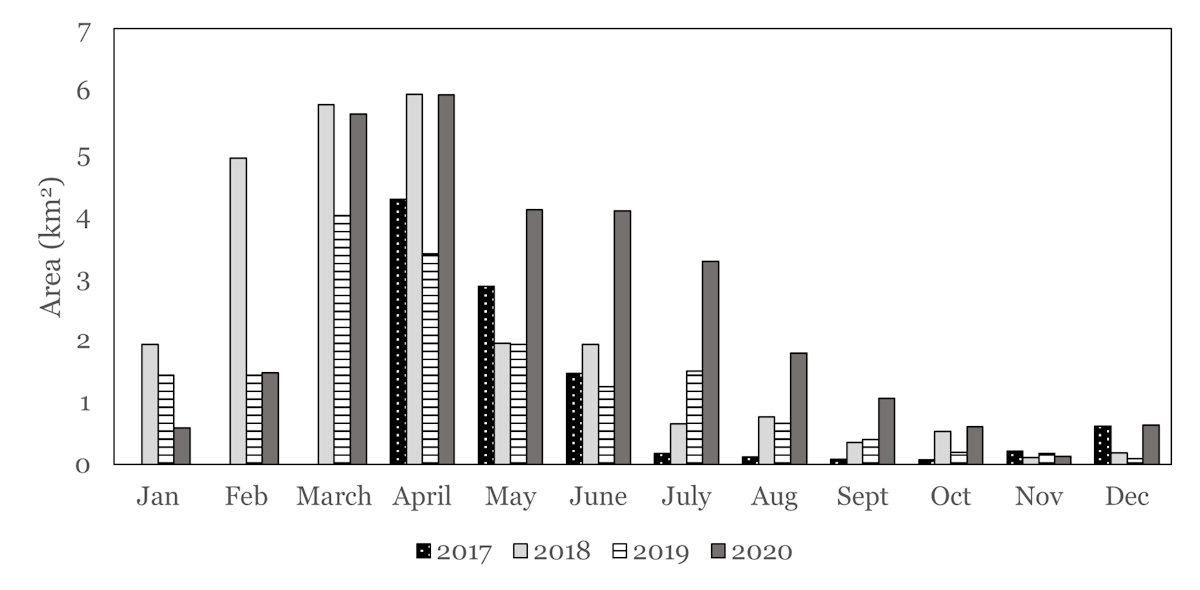

We mapped seaweed production along the Pangkep mainland from April 2017 to December 2020. The map reveals how seaweed production changes through the seasons – almost all seaweed is grown in the first half of the year.

Next, we compared seaweed production in 2020 to previous years to see if there was a significant difference. We found seaweed production between May and September in 2020 was much higher than in previous years.

Environmental conditions, local farming practices and the economic impacts of COVID-19, such as trade disruptions and job losses, may have contributed to this trend.

1. Environmental conditions

A range of factors affect seaweed growth rate. These include water temperature, sunlight, salinity, nutrients, acidity levels, seed size and genetic material, sedimentation, water oxygen levels and disease infection.

For example, ocean salinity – the concentration of salt in seawater – has a particularly strong effect on seaweed growth.

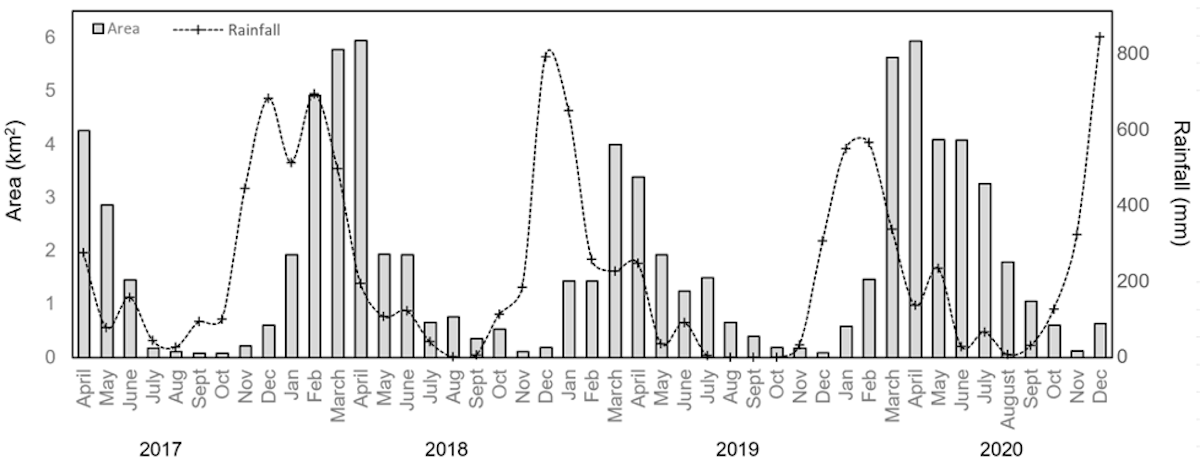

The salinity of the Java Sea varies throughout the year as monsoonal rains increase river flows into the ocean.

As a result, different rainfall patterns each year can increase or decrease seaweed growth rates. Farmers respond to this by changing their production.

2. Farming practices

The method of farming can also affect the amount of seaweed produced. A particularly important factor is the way that crops are propagated.

Indonesian seaweeds are clonally propagated from cuttings.

Some farmers do this themselves, while others buy cuttings from other farmers or distributors.

Accessing high-quality seeds is a challenge for the industry. Some farmers spend more than half of their seaweed farming income on seeds for the next harvest.

Government farmer assistance programs can, therefore, have a strong effect on the viability of seaweed production.

3. The impacts of COVID-19

While the above factors could be responsible for increased seaweed production, it’s likely the economic effects of COVID-19 are at least partially responsible for the change.

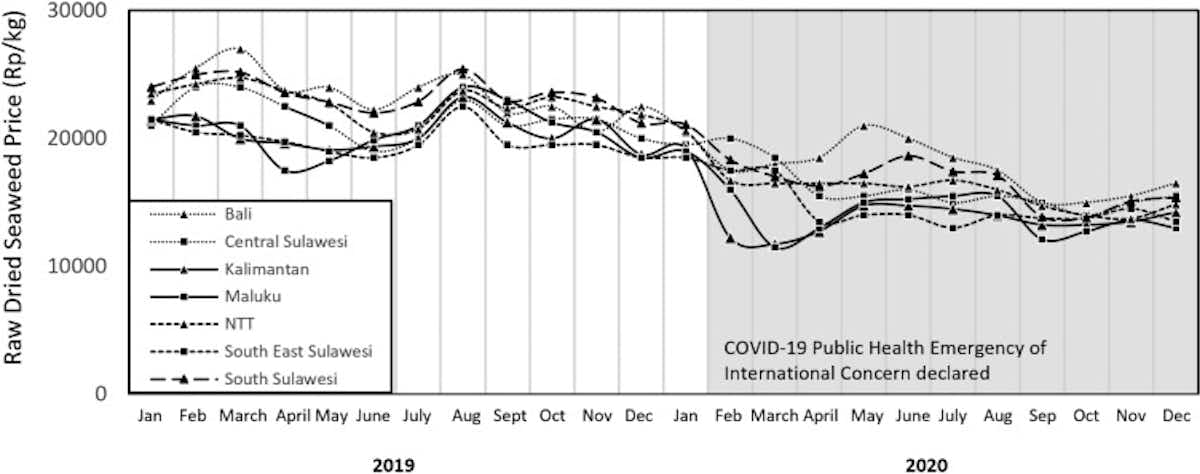

During the pandemic in 2020, seaweed prices fell by 27%.

This suggests farmers are producing more seaweed but selling it at a lower price than before the pandemic.

Why would this be the case?

It is likely that although COVID-19 impacted a range of industries in Indonesia, the impact on seaweed farming has been less severe. This is because dried seaweed can be stored relatively easily, so it is more resilient to supply-chain disruptions.

This means that even though seaweed prices are lower than before, the industry may still have become more desirable relative to other, more severely affected sectors.

For example, in some parts of Bali, there have been huge increases in seaweed production as a result of job losses during the pandemic.

While satellite data alone cannot give a complete picture of the complex livelihood effects of the pandemic on seaweed farming, it does alert us to broad patterns and trends.

The extended use of remote sensing across wider areas, along with on-the-ground research to the extent possible, may help monitor the fluid situation.

The authors’ interdisciplinary research project in the Partnership for Australia-Indonesia Research focuses on improving the Indonesian seaweed industry’s outcomes with a particular focus on South Sulawesi. To learn more about this and the work of Indonesian and Australian research teams on youth and the new rail line, you can read more details here.