Billions of years ago, the Earth's surface was a molten rock ocean. As this molten magma gradually cooled, it solidified into a continuous rocky shell. Denser minerals sank towards the Earth's core, while less dense minerals rose to the surface.

"This is how the Earth's surface plates were formed," explained Catherine Rychert, a geophysicist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts. "The plate refers to the crust, with a portion of the mantle below it... Beneath that lies less strong material."

This less strong material is hotter and more mobile. The difference in strength between these layers is what enables the Earth's surface plates to move, either colliding, moving apart, or grinding against one another. In these zones, rifts, mountains, volcanoes, and earthquakes come into existence.

But how many of these plates exist on the Earth's surface? The number varies from a dozen to nearly 100, depending on the perspective.

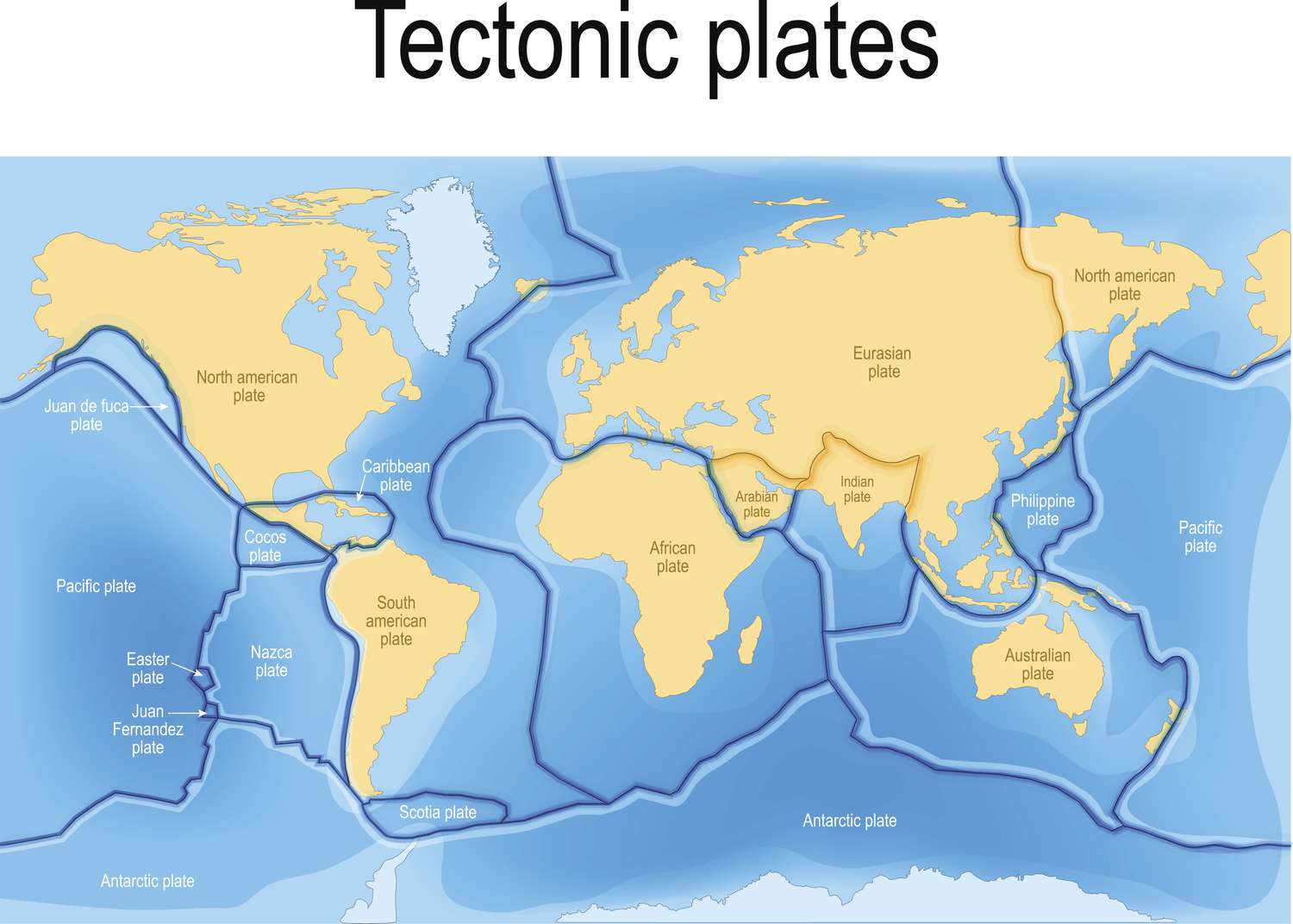

Most geologists concur that there are between 12 and 14 "primary" plates that cover most of the Earth's surface, as indicated by Saskia Goes, a geophysicist at Imperial College London. Each of these plates has an area of at least 20 million square kilometers, with the largest being the North American, African, Eurasian, Indo-Australian, South American, Antarctic, and Pacific plates. The Pacific Plate is the largest, covering approximately 103.3 million square kilometers, closely followed by the North American Plate, which spans 75.9 million square kilometers.

Apart from these seven substantial plates, there are five somewhat smaller ones: Philippine Sea, Cocos, Nazca, Arabian, and the Juan de Fuca. Some geologists consider the Anatolian Plate (part of the larger Eurasian Plate) and the East African Plate (part of the African Plate) as separate entities because they move at different speeds from the main plates. This accounts for the variation in the count of main plates, ranging from 12 to 14.

The situation becomes more intricate when considering plate boundaries, where plate tectonics causes plates to break into smaller fragments known as microplates. These microplates have an area of less than 1 million square kilometers, and it is estimated that there are around 57 of them on Earth. However, they are typically not depicted on world maps, reflecting uncertainty about their formation.

"The number of microplates will continue to change as different scientists define them and as we gain more knowledge about the localization of deformation at plate boundaries," remarked Goes.

As geologists decipher this complex puzzle, the Earth's shifting plates give rise to intriguing scenarios. The Pacific Plate is the fastest, moving northwest at a rate of 7 to 10 centimeters per year, driven by the gravitational forces of the surrounding subduction zones, known as the Ring of Fire, where plates are drawn into the Earth. Rychert suggests that this constant motion might even result in the submersion of continents, as occasionally, continents may founder, causing pieces to fall into the mantle.

With these dynamic forces at work, the appearance of our planet's plate-covered surface in a few billion years remains a mystery.