Vietnam’s writing system stands out sharply from the rest of Southeast Asia due to its use of the Latin alphabet, known as quốc ngữ.

While neighboring countries like Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar use writing systems derived from ancient Indian scripts, Vietnam’s Romanized script reflects a unique linguistic and historical journey.

The evolution of Vietnam’s script is deeply rooted in colonial, religious, and political influences, making it one of the most distinctive in the region.

Chinese Influence and Chữ Hán

For over a thousand years, Vietnam was under Chinese rule (roughly from 111 BCE to 939 CE), and during this period, Chinese language and script dominated all official, scholarly, and literary activities. The Vietnamese elite were trained in classical Chinese (chữ Hán), and this system became the foundation for administration, education, and Confucian texts.

However, Chinese characters were not a natural fit for the Vietnamese language, which is structurally different. Still, for centuries, chữ Hán was seen as the language of the educated and powerful, embedding Chinese linguistic influence deeply into Vietnamese culture.

The Creation of Chữ Nôm

In response to the limitations of chữ Hán, Vietnamese scholars developed a hybrid script called chữ Nôm around the 13th century. This system used modified and newly invented Chinese characters to represent native Vietnamese words and sounds that did not exist in Chinese.

Chữ Nôm allowed Vietnamese writers and poets to express themselves in their own language for the first time. Famous literary works like The Tale of Kieu by Nguyễn Du were written in this script.

However, chữ Nôm was highly complex, difficult to standardize, and accessible only to the educated elite. Its unwieldy nature made it hard to learn and impractical for mass literacy, unlike the more phonetically consistent scripts in other Southeast Asian countries.

The Arrival of the Latin Alphabet and Quốc Ngữ

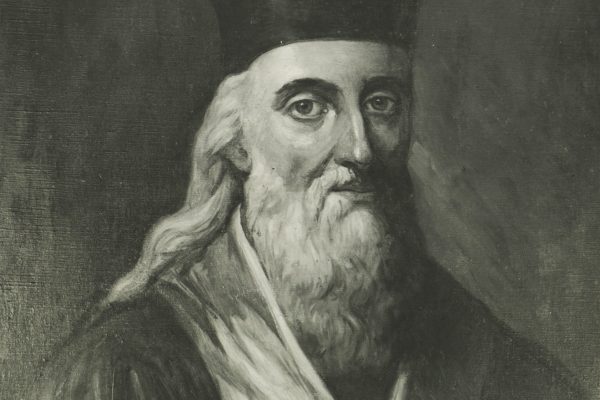

The major turning point came in the 17th century with the arrival of European missionaries, particularly the Portuguese and later the French Jesuits. Alexandre de Rhodes, a French Jesuit missionary, is often credited with developing quốc ngữ, a Romanized writing system for Vietnamese.

He and other missionaries used the Latin alphabet to transcribe Vietnamese phonetics so they could teach the faith and translate religious texts more easily.

Quốc ngữ used diacritics extensively to denote the six tones and various vowel sounds of Vietnamese. This system was much easier to learn and teach compared to chữ Nôm or chữ Hán.

Initially, quốc ngữ was confined to religious use and rejected by the Confucian scholarly class, who viewed it as foreign and inferior. But during French colonial rule in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the colonial government promoted quốc ngữ as part of its civil administration and education reforms.

Ironically, while this was meant to suppress Vietnamese nationalism by eroding classical Confucian traditions, it backfired. Widespread literacy in quốc ngữ helped spread revolutionary ideas and unify the country’s population against colonial rule.

Post-Independence

After gaining independence from France and later reunifying in 1975, Vietnam embraced quốc ngữ as the national writing system. It became a powerful symbol of Vietnamese identity and modernity.

Unlike the logographic Chinese-based scripts or the abugida systems in Cambodia and Thailand, quốc ngữ is purely alphabetic and phonetic, making literacy easier to achieve across the population. This helped Vietnam implement widespread educational reforms and rapidly boost literacy rates during the 20th century.

Today, quốc ngữ sets Vietnam apart from the rest of Southeast Asia. While its neighbors retained traditional scripts rooted in Brahmic origins, Vietnam uses a writing system born of European influence, shaped by religious missions, and later repurposed for nationalism and modern education.

The shift was not just a linguistic change but a reflection of the country's complex history—colonial contact, cultural resistance, and pragmatic adaptation. This unique trajectory explains why Vietnam’s writing system is so strikingly different from its regional counterparts.