Imagine a summer so cold and dark that birds dropped dead mid-flight, crops rotted in the fields, and snow fell in June. No, this isn't climate fiction. It really happened. And Southeast Asia, specifically Indonesia, was ground zero.

The year was 1816, but history remembers it as “The Year Without a Summer.” The culprit? Mount Tambora, an Indonesian volcano whose eruption the year before — in April 1815 — became the most powerful volcanic explosion in recorded history.

Tambora: The Blast That Changed the World

Located on Sumbawa Island in present-day Indonesia, Mount Tambora erupted with such force that it blasted more than 160 cubic kilometers of ash and debris into the atmosphere. That’s enough to bury the entire island of Singapore under 15 meters of ash. The eruption instantly killed tens of thousands, with even more deaths in the following months due to starvation, disease, and tsunamis.

But Tambora’s destruction didn’t stop there.

The explosion injected sulfur dioxide and ash high into the stratosphere, forming a global veil that reflected sunlight away from the Earth. The result? A massive and sudden drop in global temperatures — about 3°C on average — disrupting weather patterns across the planet for years.

Snow in June, Famine in July

In New England, people woke to frost in mid-summer. Snow fell in June. Crops withered, livestock froze or starved, and food prices skyrocketed. The same grim scenario played out in Europe, where skies stayed ominously overcast, and fields turned barren. Riots over food broke out in France, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Historians believe this period triggered one of the worst famine crises of the 19th century in the Northern Hemisphere.

This worldwide disaster had especially harsh effects on farmers and the poor — many of whom had no idea that a volcanic eruption halfway around the globe was to blame.

From Ashes to Art: Enter Frankenstein

While humanity struggled to survive, one young woman was about to give birth to something extraordinary — not a child, but a literary monster.

In the summer of 1816, a then-18-year-old Mary Shelley (alongside her future husband Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron) was vacationing near Lake Geneva, Switzerland. But instead of enjoying lake breezes and picnics, they were trapped indoors by the dreary, ash-dimmed skies and constant rain. To pass the time, Byron suggested they each write a ghost story.

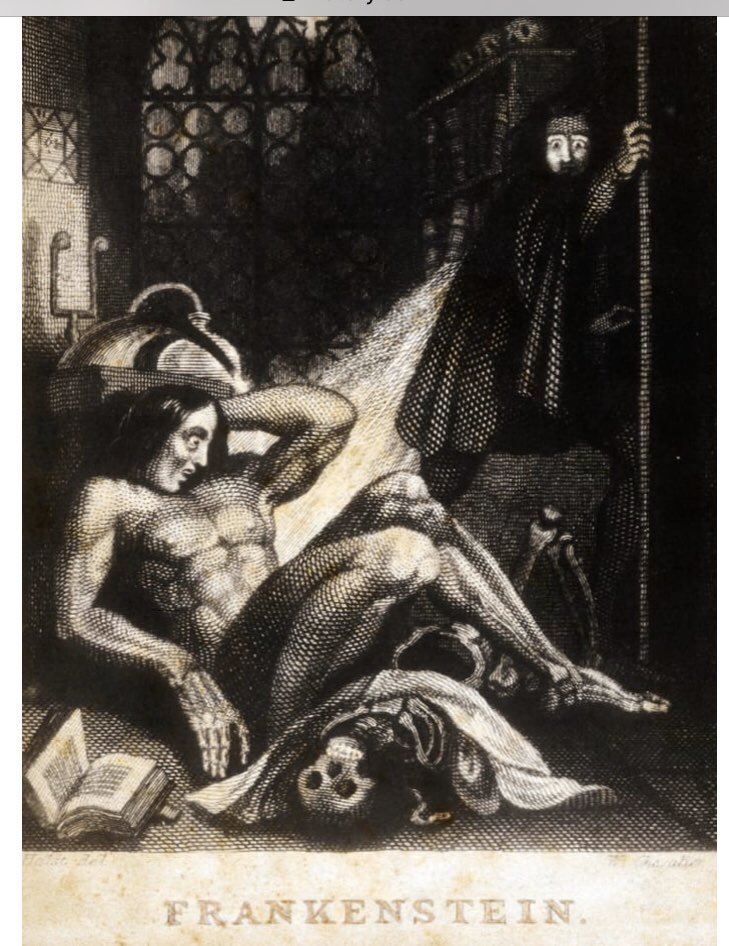

Mary Shelley took the challenge seriously. From those gloomy days and candlelit nights, she crafted the chilling tale of “Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.” Her novel — widely considered the first science fiction story ever written — was a product of that sunless summer.

So yes, it’s fair to say: an Indonesian volcano gave birth to Frankenstein.

The Southeast Asian Legacy of a Global Climate Catastrophe

Mount Tambora’s 1815 eruption reminds us of how deeply interconnected the planet is, even two centuries ago. A single volcano in the Dutch East Indies could reshape economies, alter climate, kill crops — and inspire timeless art.

Today, the Tambora eruption is studied as a warning. With climate change increasing the stakes of natural disasters, it’s more important than ever to understand how a local event in Southeast Asia can have global implications.

And next time you see a horror movie featuring Frankenstein, just remember: it all began with an Indonesian volcano, a sunless summer, and a young woman trapped indoors with her imagination.