If you've ever heard of Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days, then be prepared to find out that the Filipinos once made a similarly outstanding feat: flying from Manila to Madrid in 44 days.

Aside from the fact that PAL (Philippines Airline) was the first commercial airline in Asia, not much is known about the Philippines’ role in aviation. Yet, the 44-day Manila-Madrid flight by pilot pair Juan Calvo and Antonio Arnaiz deserves a place as one of the moments that put the Philippines on the world's stage as a pioneer in air navigation.

Who were Juan Calvo and Antonio Arnaiz, and why did their mission matter so much for Filipinos then and today?

Early Life

Though Filipino by ethnicity, Juan Calvo was born in the Spanish city of Madrid in 1898. He spent most of his life in Manila. Juan received his flying certificate from the Curtiss School of Aviation in Parañaque, a city located on the eastern side of Manila Bay. His avid passion for aviation then led him to enroll in Valeriano Flying School to obtain his license.

Valeriano was the place where Juan met Antonio Somoza Arnaiz. Antonio himself was born in Bais, a city in the Negros Island, in 1912. He was U.S.-trained, having graduated from Dallas Aviation School before meeting Juan while serving as an instructor in Valeriano.

The two weren't the first aviators from the Philippines. Before them, there was Alfredo Carmelo, the first Filipino to fly solo in a plane in 1920. Alfredo's contribution paved the way for aviation in the Philippines and opened the doors to more flights from and to the country.

A significant “moment of truth” was the flight from Madrid to Spain in 1926 by Spanish aviator Joaquin Loriga and his peer, engineer Eduardo Gallarza. This was one of the first flights to the Philippines from Spain, done with a plane called Legazpi, which featured the Filipino flag on its body. The heroic Loriga-Gallarza mission inspired Juan and Antonio to fly, too – this time from Manila to Madrid.

From Manila to Madrid

Juan put forward his plan on flying from Manila to Madrid to Antonio, who agreed enthusiastically. Since the beginning of their planning, the pair faced crucial challenges.

Adam Humphris records in Phil-Philately that the government didn’t want to sponsor the flight because they deemed it too dangerous. It was also speculated that the government did not want any political entanglements.

Antonio immediately gathered funds, mostly from his family friends, to obtain the required logistics and modify the plane they would fly in. A notable donor for the mission was Carlos Romulo, then publisher in the Philippines Herald, who proceeded to become the first UN General Assembly president from Asia.

After preparations were complete, the two departed on May 29, 1936 on their plane, a used single engine Fairchild model 24. The government dubbed the plane “Commonwealth” to symbolize the nation's goodwill, as the Philippines was a commonwealth under U.S. control at that time. The mission itself was called ARNACAL, an abbreviation of the pilots’ surnames (ARNAiz-CALvo).

Juan and Antonio had to make several stops along the way as their plane had a leaking gas tank. It was also reported that the plane had neither radios, seat belts, nor parachutes, making the journey all the more risky. In their stops, they were keenly greeted by Filipino diasporas.

The pair arrived on July 12, 1936 in Madrid and were received with a warm welcome, including a party by the Spanish Air Forces and a personal banquet from the mayor himself. Juan also had the opportunity to reunite with his father, Pedro Calvo, whom he had not seen in 13 years and was then serving for the Spanish Army.

The End of the ARNACAL Mission

The two could not stay for long because it was too dangerous to stay in Spain, where a civil war was currently underway. The Nationalist faction – dubbed by the Spanish government as rebels – sunk Commonwealth at the Port of Barcelona. Juan and Antonio returned by sea via France and safely arrived in Manila in September of the same year.

After the flight, Juan worked in Iloilo-Negros Air Express Co. (INAEC), an airline company which pioneered PAL. Calvo then served as a captain during World War II, leading a guerilla unit against Japanese forces before he was captured and executed in 1945 under the command of the Allied Forces.

On the other hand, Antonio was promoted together with Juan into the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Philippines Army Air Corps by President Manuel Quezon. Antonio then decided to pursue a doctorate in aeronautics engineering, proceeding to become the director of the Philippines Aviation Corporation – which used to be Valeriano.

An Enduring Legacy

Juan and Antonio's successful mission led to them being recognized as national heroes. The two were posthumously awarded by the government, with Antonio even having a street in Manila named after him in his honor.

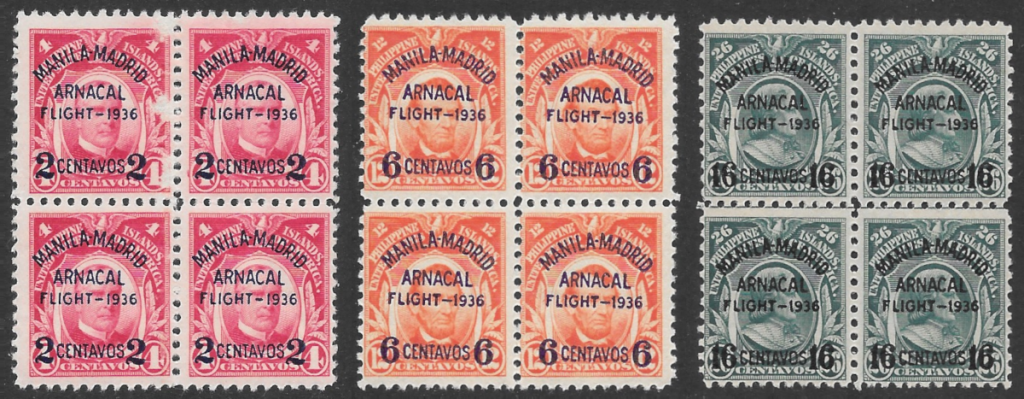

The government of the Philippines released commemorative stamps of the ARNACAL flight in 1936. The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. also keeps records of Juan's scrapbooks, letters, and photographs.

However, the greatest achievement of the pair was, and perhaps still is, the fact that they were the first Filipinos to cross the South China Sea by air. Even Antonio was Asia's first licensed pilot, long before Japan or any other Asian nation took flight.

The dangerous mission, in a used plane at that, was a prominent moment in the history of Filipino aviation. Spanning across major cities like Hong Kong, Yangon, Hanoi, Cairo, Gaza, Athens, Rome, and Marseille, the ARNACAL flight also helped establish flying routes across the globe, thus placing the Philippines as a major pioneer of international air navigation.

References

Humphris, Adam. “1936 ARNACAL Flight Stamps.” Phil-Philately. Published on July 7, 2023. Accessed on July 10, 2025. https://www.phil-philately.com/philippines-history/1936-arnacal-flight-stamps/.

“Juan Calvo Papers.” Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Accessed on July 10, 2025. https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-archive/juan-calvo-papers/sova-nasm-2014-0035.