Indonesia is a country rich in culinary diversity. Each region has its own traditional dishes with flavors that reflect its local identity. These foods not only represent the geographical characteristics of their regions but also serve as a source of identity and collective memory for the people.

Indonesia’s culinary wealth lies not only in its dishes but also in the variety of spices and condiments used. One distinctive condiment is petis, commonly found in East Java, Indonesia, especially in Surabaya City, Sidoarjo City, and Madura Island. Petis is a thick black paste that made from seafood with a strong, pungent aroma, often used as a dipping sauce or mixed into traditional dishes.

As someone born and raised in East Java, I was used to petis being present in almost every meal—not only as a cooking ingredient, but also as a dipping sauce or flavorful companion. Eating gorengan—Indonesian-style deep-fried street snacks like tofu, tempeh, and vegetables—never felt complete without petis.

Petis as Identity and Memory

Petis isn’t exclusive to East Java, there are regional variations like Cirebon’s petis from West Java that made from rebon shrimp and Boyolali’s beef broth-based petis from Central Java. However, in East Java—especially in Surabaya, Sidoarjo, and Madura—petis is ubiquitous, appearing in nearly every traditional dish.

Petis is made by simmering the liquid from boiling shrimp or fish until it reduces into a thick, dark paste, then adding spices. Its taste is savory, sweet, slightly salty, and its aroma is sharp—often too pungent for those unaccustomed. Yet, for East Javanese people, it’s a familiar and beloved flavor.

According to the official website of the Faculty of Cultural Sciences at Airlangga University, historian Ikhsan notes that petis has existed since the 14th-century Majapahit Kingdom. Shrimp-based petis was also mentioned in Serat Centhini, a 19th-century Javanese literary work published in 1814 during the Islamic Mataram Kingdom. This 12-volume text documents various aspects of Javanese life, and in Volume 10, petis is referenced as part of the region’s culinary traditions.

Petis also appeared in Thomas Stamford Raffles’ book The History of Java, published in 1817 after his tenure as Lieutenant Governor of the Dutch East Indies (1811–1816). In the book, Raffles noted petis as a popular culinary specialty among the Javanese.

Furthermore, Ikhsan wrote in his journal article, titled 'Rujak Cingur: Narasi Historis Watisan Budaya Kuliner Populer Masyarakat Urban Surabaya', about the presence of petis during the Dutch East Indies colonial period (when Indonesia was under Dutch colonial rule from 1830 to 1942).

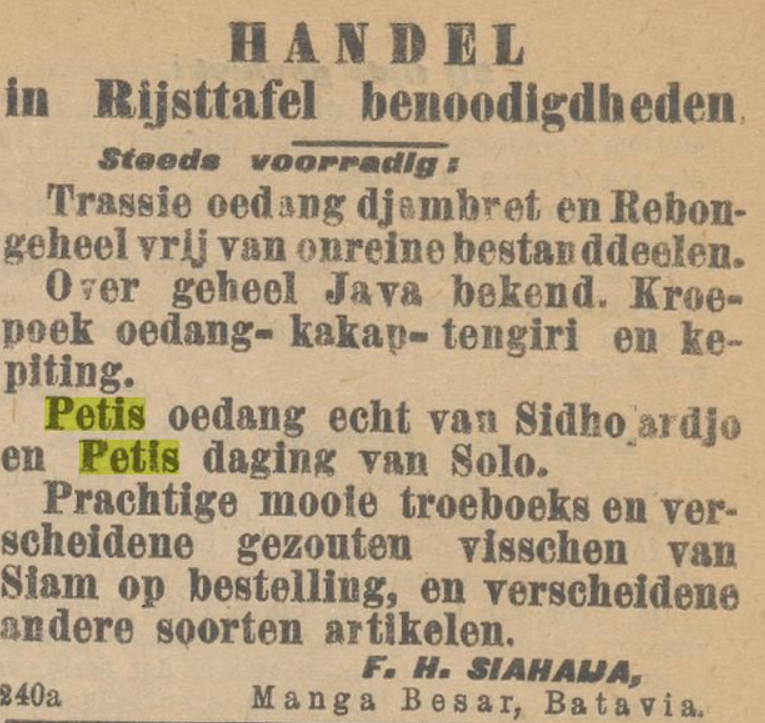

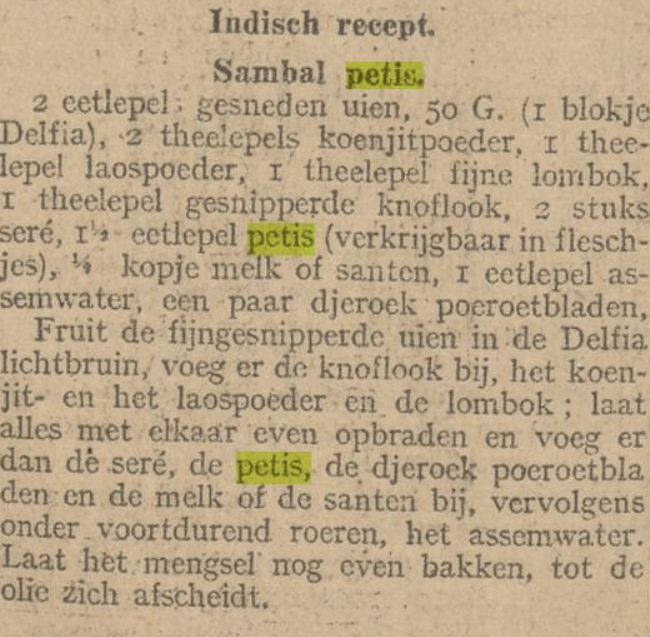

Recipe books from 1894, such as "Kokki Bitja, of Tab Masak-Masakan India, Jang Baharoe dan Sampurna" (Hindia Cook Book, New and Perfect), mention petis as a cooking ingredient. Additionally, colonial-era newspaper advertisements featuring petis indicate that it was sold not only in East Java, but also distributed across the archipelago.

The use of petis in local cuisine has existed for centuries. It also reflects how coastal communities preserved the taste of the sea in a longer-lasting form. The presence of petis in coastal regions shows how local ingredients and geographical conditions play a crucial role in shaping cultural identity.

Food as Regional Identity

Food and its ingredients help shape cultural identity. Cultural identity involves the awareness of a group’s distinct characteristics—its customs, language, lifestyle, and values. Each region in Indonesia has its own unique culinary flavor profile, shaped by local ingredients and passed down through generations.

In coastal regions like East Java, the heavy use of seafood has influenced the flavors that define the area’s food—like petis. Local dishes become not only culinary traditions, but also representations of geography, heritage, and community. Local food becomes a binder, a regional marker, and an affirmation of identity. And for me, petis embodies that. Its strong, bold, and distinct taste carries with it a sense of place and a personal history.

Today, petis is a key component in many East Javanese dishes such as rujak cingur, lontong balap, and tahu tek. Rujak cingur was even declared an intangible cultural heritage in 2021 by Indonesia’s Ministry of Education and Culture. Petis is also commonly brought home as a regional souvenir. Food is not only about feeding the stomach or fulfilling nutritional needs—it also becomes a vessel of memory and a marker of cultural identity.