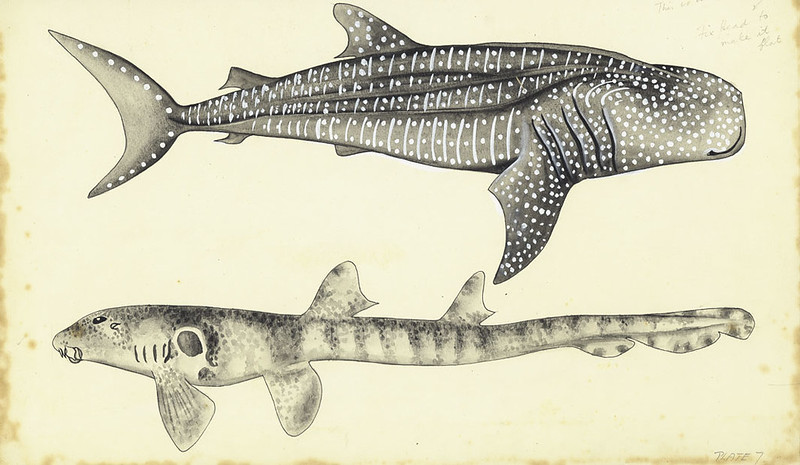

The whale shark (Rhincodon typus) often sparks confusion because of its name. Many people assume it is related to whales or even mistake it for being the largest animal in the ocean. In reality, the whale shark is a fish — the largest living fish in the world. The actual largest animal is the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), a marine mammal that can reach over 30 meters in length and weigh up to 180 tons.

By contrast, the whale shark usually grows between 12 and 18 meters long and weighs up to 20 tons. Unlike the blue whale, which breathes air and feeds its calves with milk, the whale shark breathes through gills and reproduces as a fish does. Its size is still astonishing, making it the ocean’s largest shark and fish, a true gentle giant of tropical seas.

A Gentle Giant of the Seas

Despite their massive size, whale sharks are not predators of large animals. They are filter-feeders, opening their wide mouths to strain plankton, krill, and small fish from seawater. This feeding style places them in the same ecological role as baleen whales, which also filter food, though with very different biological systems. Their slow, calm swimming and surface-feeding behavior make whale sharks approachable to divers and snorkelers, giving rise to their reputation as friendly giants.

Southeast Asia is a particularly important region for whale sharks. Tropical and warm-temperate seas across Indonesia, the Philippines, and the Maldives host frequent sightings and even seasonal gatherings. These encounters draw both scientists and tourists, who are equally fascinated by the opportunity to witness the world’s largest fish up close. Yet, conservationists warn that without careful management, such encounters may place stress on the species and its habitats.

Whale Sharks in Indonesia and the Philippines

Indonesia is home to some of the most remarkable whale shark habitats. In Cenderawasih Bay, Papua, whale sharks are known to congregate around fishing platforms known as “bagan.” Fishermen often discard fish near these structures, inadvertently attracting the sharks. This unusual interaction has turned the area into a tourism hotspot. However, experts caution that repeated feeding could alter whale shark behavior, making them dependent on artificial food sources.

In the Philippines, the towns of Donsol and Oslob have become famous for whale shark tourism. Donsol has been promoted internationally as an example of community-based eco-tourism, with rules that limit boat numbers and enforce minimum distances from the animals. Oslob, however, has faced criticism for feeding practices that disrupt natural migration patterns and increase risks of injuries from boats. Marine scientists emphasize that such contrasting examples highlight the need for responsible tourism management.

The Maldives offers another key location, particularly in the South Ari Atoll Marine Protected Area. Here, conservation programs like the Maldives Whale Shark Research Programme have successfully combined tourism, science, and local community involvement. By using photo-identification techniques, researchers have built global databases that track individual whale sharks across regions. This collaborative approach has strengthened both knowledge and protection of the species.

Conservation Concerns and Global Importance

The whale shark is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List. Historically, it was hunted for its meat, fins, and oil, though many countries now ban direct hunting. Still, accidental bycatch in tuna fisheries and ship strikes remain major threats. The species’ slow growth and late maturity make it particularly vulnerable: it takes years before individuals can reproduce, and populations cannot recover quickly once reduced.

A study in PeerJ (2016) reported a global population decline of more than 50% in the past 75 years. Beyond fishing pressures, climate change now adds uncertainty to the whale shark’s future. Shifts in ocean currents and plankton abundance may force whale sharks to change their migration patterns. Some traditional aggregation sites have already reported fewer sightings, raising concerns about long-term survival.

Community involvement is essential in addressing these threats. In Indonesia and the Philippines, eco-tourism has provided alternative income for local fishing communities, reducing reliance on destructive practices. However, without clear regulations and enforcement, eco-tourism itself can become harmful. Conservationists stress that protecting whale sharks requires balancing ecological needs with social and economic realities.

The Way Forward

The whale shark’s presence in Southeast Asia represents more than a tourist attraction. It is a living symbol of the ocean’s biodiversity and a reminder of the delicate balance between humans and marine ecosystems. Protecting this species requires marine protected areas, stronger fishing regulations, and international cooperation, since whale sharks migrate across borders. Global treaties such as CITES and the Convention on Migratory Species have already recognized the need for collective action.

At the same time, citizen science initiatives — where tourists and divers submit photos of whale sharks — have proven invaluable. These photographs allow researchers to track movements across thousands of kilometers, offering new insights into migration and population health. With the support of science, policy, and community participation, Southeast Asia has the chance to lead the world in whale shark conservation.

Ultimately, while the blue whale remains the largest animal ever to live, the whale shark stands proudly as the largest fish on Earth. Ensuring that future generations can continue to marvel at these gentle giants will depend on the choices made today — choices that prioritize conservation, sustainability, and respect for one of the ocean’s most extraordinary species.