When European naturalists first encountered the platypus in the late 18th century, they were baffled. This small, semi-aquatic mammal native to eastern Australia didn’t fit neatly into any category known to science.

It had the bill of a duck, the tail of a beaver, and the feet of an otter. And stranger still, it laid eggs. To early zoologists trained in the rigid classifications of the Enlightenment era, this creature seemed more like a myth than a real animal.

The first specimen of a platypus was sent to England in 1799. Preserved in alcohol, it reached the hands of prominent scientists, including the influential anatomist George Shaw. Even as he examined it, Shaw suspected it might be an elaborate hoax.

The specimen looked so unnatural that he thought perhaps a clever taxidermist had stitched together parts from several animals.

John Hunter and His Weird Discovery

Though often attributed to George Shaw, the platypus was also closely associated with the work of John Hunter, a pioneering British surgeon and naturalist who played a key role in early Australian biological research.

Hunter did not “discover” the platypus in the sense of being the first to find it, Indigenous Australians had known of the creature for millennia, but he was among the first Europeans to take it seriously as a subject of scientific study.

Hunter supported the idea that the platypus was a real, natural animal and not a taxidermy trick.

He used his reputation and resources to argue that the bizarre characteristics of the platypus were genuine and worth further investigation. Despite his credibility, many of his colleagues remained skeptical for years.

A Mammal That Lays Eggs

One of the most confounding aspects of the platypus was its method of reproduction. The idea that a mammal could lay eggs flew in the face of contemporary biological understanding.

Mammals were defined in part by their live births. To say that a warm-blooded, fur-covered animal could reproduce like a bird or reptile was seen as biological blasphemy.

It wasn’t until decades later, in the 1880s, that scientists were able to observe egg-laying in platypuses directly. Until then, arguments over its classification persisted.

Eventually, the platypus and its close relatives, the echidnas, were assigned their own group within the mammalian class: the monotremes, a word meaning “single opening,” referring to their shared cloaca, a feature more commonly found in reptiles and birds.

Venom and Electroreception

As if its appearance and egg-laying weren’t strange enough, the platypus added more oddities to the list.

Male platypuses have venomous spurs on their hind legs, capable of delivering a painful sting that can incapacitate small animals, and cause severe pain to humans. This feature is extremely rare among mammals and further contributed to its mystique.

Even more astonishing is the platypus's ability to detect electric fields. Using receptors in its bill, it can sense the weak electrical signals given off by the muscles and nerves of its prey.

This allows it to hunt underwater with its eyes, ears, and nostrils closed. Electroreception is common in fish and amphibians but almost unheard of in mammals, placing the platypus in a category all its own.

From Skepticism to Wonder

Over time, the scientific community had no choice but to accept the platypus for what it was: a living, breathing paradox. The initial disbelief and accusations of fraud gave way to fascination.

Naturalists who once dismissed the animal as an elaborate joke came to appreciate it as a window into evolutionary history.

The platypus seemed to straddle the divide between mammals, birds, and reptiles, offering tantalizing clues about how these groups might be connected.

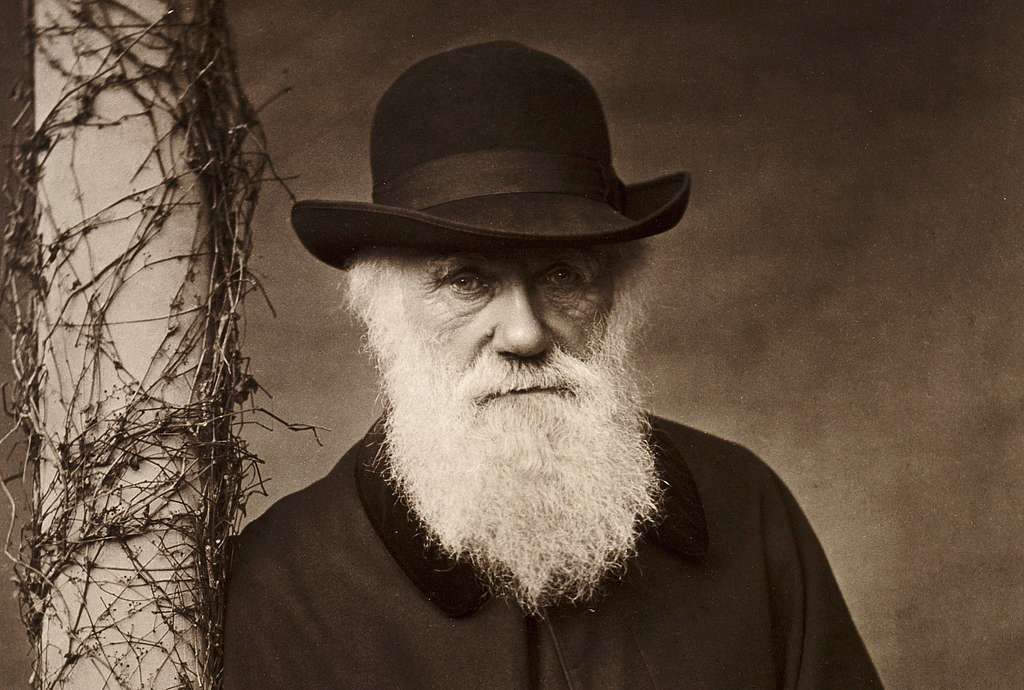

Charles Darwin himself was intrigued by monotremes. Though he never saw a platypus in the wild, he recognized that such animals posed important questions about how species evolve and diversify.

The platypus, rather than being an anomaly, became a key to understanding the fluidity of nature’s design.

A Living Fossil

Today, the platypus is often described as a “living fossil,” a term that reflects its ancient evolutionary roots.

Genetic studies suggest that monotremes split from the rest of the mammals around 250 million years ago, making the platypus one of the most primitive mammals alive today.

Yet, its continued existence also shows how evolution doesn’t always mean change; sometimes, a strange design is also a successful one.

While it may have once been dismissed as a hoax, the platypus is now celebrated as one of nature’s most extraordinary creatures. It reminds us that the natural world often defies our expectations, and that sometimes, the truth really is stranger than fiction.