In the ancient world, healthcare was often informal and sporadic. While ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans had knowledge of medicine and healing practices, they lacked institutions dedicated solely to the systematic care of the sick.

Healing was typically the responsibility of family members, slaves, or private physicians who catered to the wealthy.

The poor, the outcast, and those suffering from chronic illness were frequently left unattended. Into this environment came Christianity, a new faith that emphasized charity, compassion, and the inherent worth of every individual, regardless of their social status.

From its earliest days, Christianity taught that caring for the sick was not just a moral duty but a reflection of one’s faith.

The teachings of Jesus, particularly in the parable of the Good Samaritan and his healing miracles, inspired early Christians to see service to the sick as a divine calling.

This religious motivation would eventually drive the establishment of one of the most transformative institutions in human history: the hospital.

Christian Hospitality and the Rise of Xenodochia

The Christian approach to care began with small, informal acts of charity, often centered in homes or places of worship. During times of plague or famine, Christians were noted for staying behind to care for the ill, while others fled.

This commitment evolved into more structured efforts. By the 4th century, these charitable activities were being institutionalized into what were known as xenodochia — facilities designed to house and care for strangers, the sick, and the poor.

The term xenodochium (plural xenodochia) comes from Greek roots meaning “house for strangers.” Though not hospitals in the modern sense, these places were more than just inns or shelters.

They provided food, rest, and rudimentary medical care. Importantly, they marked a turning point in how societies approached illness — not as something to isolate or ignore, but as a condition warranting organized, communal response.

St. Basil the Great and the First Hospital Complex

One of the most important developments in this evolution occurred in the 4th century under St. Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey).

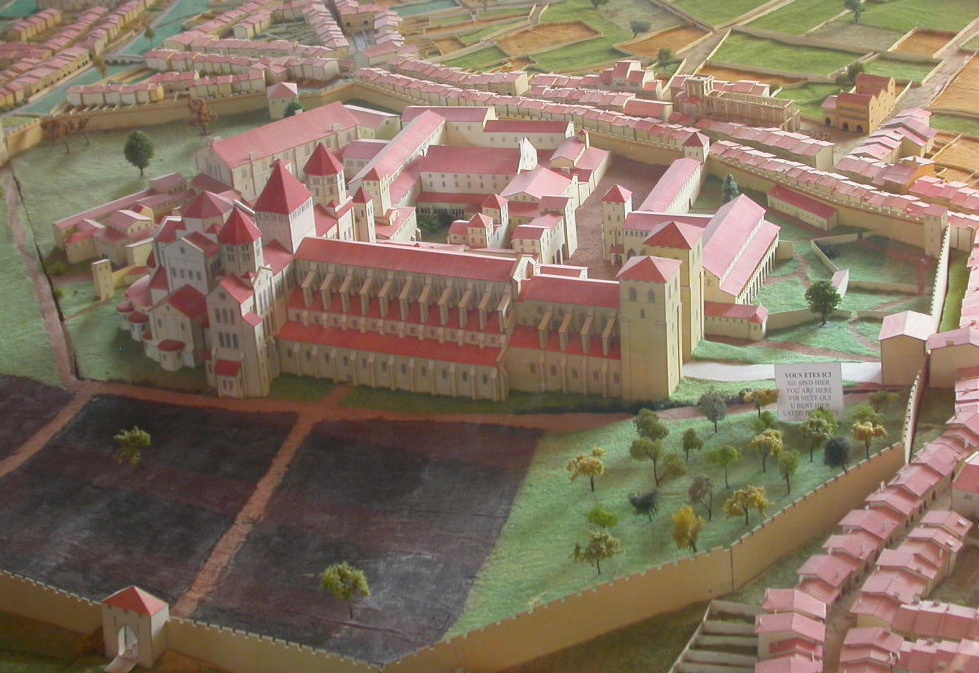

Recognizing the need for a more organized and compassionate response to the sick and destitute, Basil established what is often considered the first true hospital complex.

This institution, sometimes called the Basileias, was more than a simple hospice or shelter. It included separate buildings for the sick, the poor, and travelers, as well as facilities for medical treatment and professional caregivers.

Basil recruited physicians, nurses (then called “deaconesses”), and monks to run the facility, ensuring that care was systematic and sustained. The Basileias became a model for later Christian hospitals throughout the Byzantine Empire and beyond.

The Institutionalization of Healthcare in Monasteries

Following the example of St. Basil, many monasteries across the Christian world began to include infirmaries and guesthouses in their compounds. Monasteries were often located in remote areas, making them essential providers of healthcare to surrounding communities.

Monks preserved and advanced medical knowledge, maintained herbal gardens for medicinal use, and kept detailed records of treatments and outcomes.

By the early Middle Ages, nearly every large monastery in Europe operated an infirmary. These facilities were not only for monks but often for laypeople as well, especially during times of crisis like plague or war.

Monastic care may have been rudimentary by modern standards, but it was consistent, available to the poor, and based on the principle that all human life had inherent dignity.

Hospitals as Both Religious and Civic Institution

As Christianity spread throughout Europe and became the dominant cultural force, the hospital evolved into a religious and civic institution.

Hospitals were often founded by bishops, kings, or wealthy patrons as acts of piety. Many were located near cathedrals or attached to religious orders such as the Benedictines or Augustinians.

By the 12th century, specialized hospitals had emerged, including leper hospitals and those focused on particular diseases or demographics.

In cities like Paris, London, and Milan, hospitals grew larger and more organized, complete with staff hierarchies, medical rules, and administrative systems.

These developments were grounded in the Christian ethos of care, but they also laid the foundation for secular public health systems in later centuries.

The Legacy of the Early Christian Hospital

The early Christian hospital was revolutionary not just because it offered care, but because it did so with compassion, regularity, and an organized structure.

It treated the sick as people worthy of dignity and love, not merely as problems to be solved or outcasts to be hidden. This spiritual and moral framework profoundly shaped the trajectory of healthcare in the Western world.

While modern hospitals have become largely secular institutions, their roots in Christian charity remain undeniable.

The very idea that society has a responsibility to care for the sick, regardless of wealth or status, stems in large part from early Christian innovations.

In this way, the early Church didn’t just preserve ancient knowledge, it pioneered an entirely new model of organized, humane, and universal healthcare.