Before the 20th century, there was no standardized system for naming storms, typhoons or hurricanes, especially in the United States. However, in other parts of the world, local communities had unique ways of remembering the disasters they experienced.

In the Caribbean, for example, storms were often named after the feast day of the patron saint that coincided with the date the storm struck. Meanwhile, Clement Wragge—a 19th-century British meteorologist—became known for his creative yet controversial approach of naming Pacific typhoons after figures from Greco-Roman mythology.

He even used the names of politicians he disliked. This eccentric move eventually became the origin of a tradition that would spread across the globe.

Before the 1940s, storms in the United States were usually identified by their location and year, such as the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926. But things changed during World War II. U.S. Navy and Air Force meteorologists began naming storms after their girlfriends or wives to simplify communication in the field.

The system proved practical, and in 1953, the National Weather Bureau officially adopted female names for hurricanes in the Atlantic region. Names like Alice, Barbara, and Carol appeared on the first list.

Why Female Names?

The decision was not without controversy. Although the official reason was communication efficiency, the choice of women’s names also reflected the strong gender bias of the era.

Women were often stereotyped as “unpredictable” and “tempestuous,” traits that were thought to represent the nature of hurricanes. That belief persisted for more than two decades until it was challenged by the women’s movement in the 1970s.

In 1979, the National Weather Service and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) introduced a new system: hurricane names would alternate between male and female each year. Today, the system remains in place and is governed internationally.

Misconceptions and Public Perception

Interestingly, research shows that a storm’s name can influence how people respond to its threat. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) found that hurricanes with feminine names result in more fatalities than those with masculine names.

The study analyzed more than six decades of hurricane data in the United States and discovered that storms with “feminine” names caused an average of 41.84 deaths, compared to around 15.15 fatalities for storms with “masculine” names. One of the researchers, Sharon Shavitt from the University of Illinois, stated that public perception is often affected by subtle, unconscious gender stereotypes.

Names that sound gentle, such as “Katrina” or “Maria”, are perceived as less threatening than names like “Andrew” or “Michael,” causing many people to underestimate the actual danger. As a result, preparedness and alertness decline, and the death toll rises.

A Regulated Global Naming System

Although the naming system was initially shaped by local traditions and social biases, storm naming today is tightly regulated by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Each region has its own Regional Specialized Meteorological Centre (RSMC) responsible for determining storm names in that area. Currently, there are six RSMCs and five Tropical Cyclone Warning Centres worldwide.

For example, RSMC New Delhi is responsible for naming cyclones in the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea. The list of names comes from 13 countries surrounding the North Indian Ocean — including India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Yemen.

Each country contributes 13 names that must meet specific criteria: culturally and politically neutral, easy to pronounce, and no more than eight letters.

Meanwhile, in the Atlantic region, the storm name lists are overseen by the Hurricane Committee under the WMO. There are six rotating lists used in sequence each year.

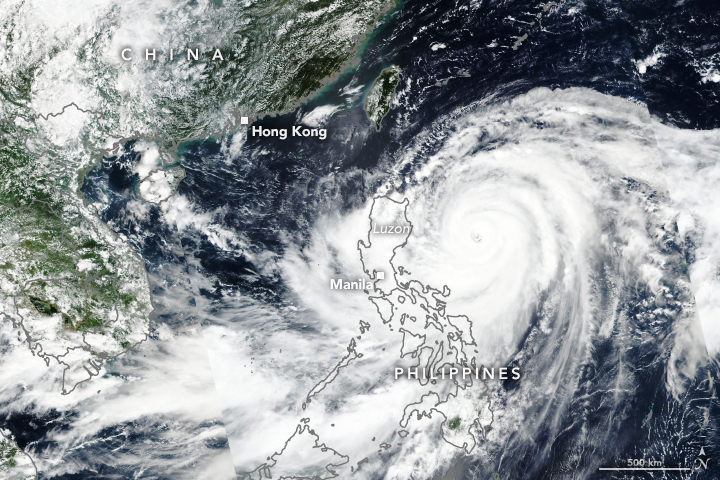

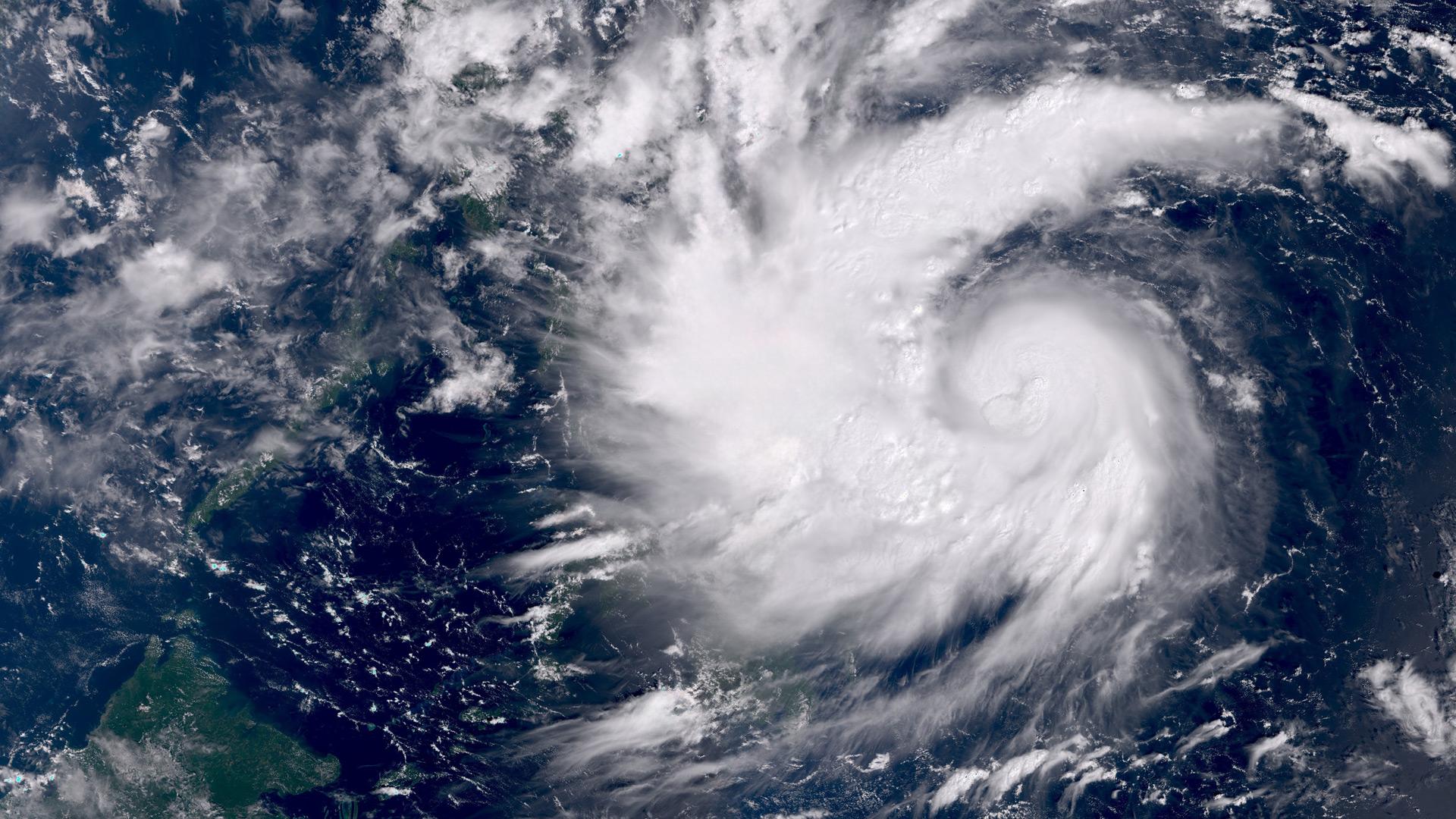

If a storm is exceptionally deadly or causes catastrophic damage, its name is “retired” and replaced with a new one. Notable examples include Katrina (2005), Haiyan (2013), Maria (2017), and Mangkhut (2018), which will never be used again due to their severe impacts.

Why Do Storms Need Names?

Naming storms is not just a formality. Before the system was established, storms were identified using latitude and longitude coordinates, a complicated method prone to miscommunication and error. Short, memorable names make communication between weather stations, maritime vessels, and broadcast agencies much faster and more accurate.

According to the U.S. National Hurricane Center, names also help the public recognize and remember specific threats, especially when two or more storms are active at the same time. In the past, confusion frequently occurred because radio reports about one storm were often mistaken for a different storm in another location.

Today, storm names serve not only a technical purpose but also play a vital role in public information. News media can report storm developments clearly, communities can more easily follow official warnings, and disaster response agencies can plan strategies more efficiently.

If you want to check the storm names designated for your country or continent, you can visit here.