Amid the wave of European colonial expansion that swept across Southeast Asia from the late 19th to the early 20th century, Thailand (then known as Siam) stood out as the only country in the region that was never colonized by a Western power.

While Burma and Malaya fell under British rule, and Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos were absorbed into French Indochina, Siam remained an independent kingdom.

This outcome was not a historical accident. It was the result of carefully calculated diplomacy, measured state-led modernization, and political leadership capable of reading global shifts at a critical moment in history.

Caught Between Two Empires: The Real Threat of Colonialism

Geopolitically, Siam occupied a highly vulnerable position. The kingdom was wedged between British power to the west and south and French expansion to the east. Under such conditions, it seemed almost impossible for a non-industrial state to survive without an exceptional strategy.

Siam’s ruling elites understood a crucial reality: direct confrontation with colonial powers would lead only to destruction, as had happened to many Asian societies before them.

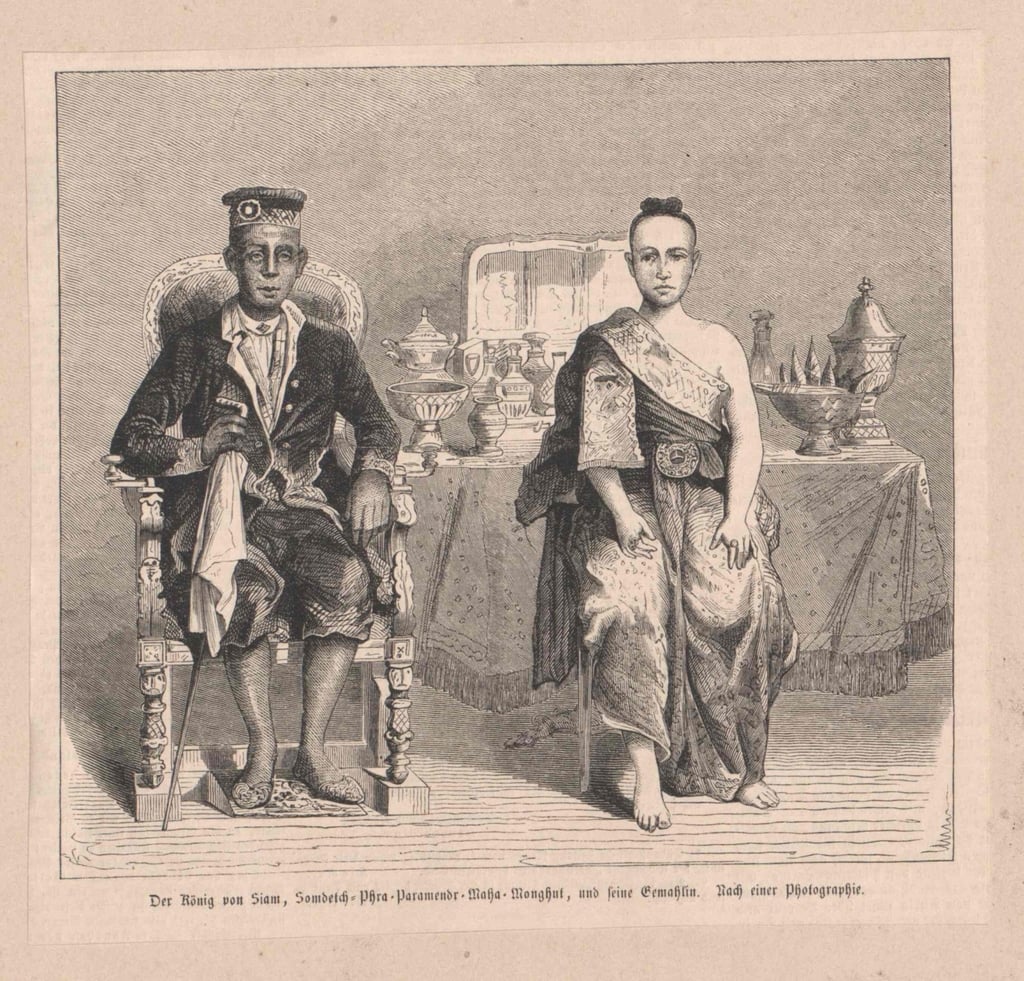

King Mongkut (Rama IV) and his son King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) drew lessons from the British conquest of Burma and the humiliation of China at the hands of Western powers.

From these examples emerged a clear realization, modernization was not a choice, but a necessity for preserving sovereignty.

Modernizing the State: Making Siam “Fit” for Independence

Under the reign of King Chulalongkorn (1868–1910), Siam undertook sweeping reforms that transformed a traditional kingdom into the foundations of a modern nation-state.

Slavery was gradually abolished. Government administration was centralized. The power of local nobles was curtailed. The legal system was reformed, a modern bureaucracy was established, taxation and state finances were brought under central control, and the military was reorganized along modern lines.

Infrastructure became a visible symbol of this transformation. Railways, roads, telegraph lines, and clean water systems were built across the kingdom.

Education was expanded through state-run schools. The Thai language was standardized, and young Siamese, including those from outside the traditional elite—were sent to study in Europe.

Together, these reforms served a strategic purpose: to present Siam as a “civilized,” orderly, and governable state, making it increasingly difficult for colonial powers to justify intervention under the banner of a so-called “civilizing mission.”

Diplomacy and Concessions: Surviving Through Compromise

Beyond internal reforms, Siam pursued high-level diplomacy. Both Britain and France viewed the kingdom as a useful buffer state, separating their respective colonial spheres.

Bangkok understood this strategic value and used it to its advantage, carefully balancing between the two powers to avoid falling under the complete dominance of either.

This independence, however, came at a cost. During the Paknam Crisis of 1893, Siam was forced to cede Laos and parts of Cambodia to France.

Additional territorial losses followed in 1904 and 1907, and through the 1909 Anglo-Siamese Treaty, which transferred several southern Malay states to British control.

Despite the loss of vast territories, Siam’s core lands remained intact. For its leaders, these concessions were viewed as strategic compromises made in the interest of state survival.

Building a Nation: Monarchical Nationalism

Unlike the anti-colonial nationalism that later emerged in neighboring countries, Siamese nationalism was largely constructed from above by the monarchy. The concept of chat (originally referring to birth) evolved into the idea of a nation as a political community.

National identity was articulated through three pillars: Buddhism, the monarchy, and the nation.

King Chulalongkorn promoted loyalty that transcended ethnic boundaries, upheld religious tolerance, and allowed a degree of local autonomy, including for Muslim communities in the south.

National monuments, museums, official historiography, and the education curriculum were employed to cultivate a shared sense of belonging.

The history of the Chakri dynasty was carefully framed to strengthen state legitimacy and unite the population around a common national narrative.

Enduring in an Unforgiving World

Thailand was not entirely spared from the pressures of imperialism. Unequal treaties, dependence on the global economy, and the presence of Western advisers continued to limit full sovereignty.

Yet compared with other countries in Southeast Asia, Siam succeeded in retaining control over its state institutions, its own military, and the direction of its modernization.

Thailand’s story is not one of absolute triumph, but of endurance under constraint. Through astute diplomacy, internal reform, and state-led nationalism, the country demonstrated that in the age of colonialism, independence could still be preserved—albeit at a considerable cost.