When we think about how Islam reached Indonesia, we usually hear about Arabian merchants or Indian traders. But there's a fascinating missing piece in this story: a brilliant scholar from Samarkand, Uzbekistan, who traveled thousands of miles to become one of Indonesia's most revered Islamic figures—Sunan Gresik.

Samarkand at Its Peak: A Cradle of Scholars and Saints

In the fourteenth century, Samarkand wasn't just another city—it was the beating heart of Islamic civilization under the Timurid Dynasty. Under rulers like Timur Lenk and his grandson Ulugh Bek, this Central Asian metropolis became a magnet for scholars, scientists, and mystics from across the Islamic world.

Born into this intellectual powerhouse, Ibrahim Asmarakandi (his surname literally means "from Samarkand") grew up immersed in sophisticated Islamic scholarship and Sufi mysticism. But instead of staying in comfort, he embarked on an extraordinary mission that would connect Central Asia to Southeast Asia forever.

Not a Straight Path: Islam’s Long Road Through Champa

Ibrahim's path to Indonesia wasn't direct. Around 1300 CE, he first traveled to the Kingdom of Champa in what is now Vietnam. According to Dr. Zumrotul Mukaffa from UIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya, this wasn't random—established trade routes already linked Turkistan with China and Southeast Asia, and Muslim communities had existed in Champa since the tenth century.

Ibrahim spent thirteen years in Champa, and his success was remarkable. He converted the king himself, Che Bong Nga, who took the Islamic name Sultan Zainal Abidin. Ibrahim married the king's daughter, Dewi Candrawulan, and they had two sons—including the future Sunan Ampel, one of Java's legendary Nine Saints (Wali Sanga).

From Champa, Ibrahim moved to Palembang in Sumatra around 1443, where he converted another ruler, Adipati Arya Damar (who became Arya Abdullah). Finally, he reached his ultimate destination: Gresik, a bustling port town in East Java.

The Sufism Secret: Why His Approach Worked

What made Ibrahim so successful where others might have failed? His sophisticated Sufism-based methodology emphasized tolerance, cultural adaptation, and gradual transformation rather than confrontational replacement of existing beliefs.

Ibrahim authored "Suluk Ngasmara," a Javanese mystical text that presented Islamic concepts while respecting local traditions. His famous work "Usul Nem Bis" brilliantly adapted Hindu-Javanese terminology for Islamic concepts: "Hyang-Pangeran" for Allah, "Sembahyang" for prayer, and even "Pandhita" (Hindu priest) for Islamic scholars.

As Michael Laffan notes in "The Makings of Indonesian Islam," Ibrahim's question-and-answer teaching format proved far more accessible than traditional Islamic texts, facilitating rapid learning across diverse populations.

When Mosques Spoke the Language of Java

The most visible proof of Ibrahim's genius stands in Gresik today: the mosque he built. Instead of copying Central Asian or Middle Eastern designs, Ibrahim adopted the Hindu temple's three-tiered pyramid roof (tajug) crowned with a mustoko—a stunning synthesis of cultures.

But this wasn't mere decoration. According to research by Ahmed Wahby, the three tiers symbolized the Islamic Sufi path: Shariah (law), Tariqah (mystical practice), and Haqiqah (truth)—Islamic concepts presented in familiar architectural language. This innovative design became the template for mosques throughout Java, creating Indonesia's distinctive Islamic architectural tradition.

New Discoveries: More Than Just a Preacher

Recent research published in 2023 reveals Ibrahim may have been far more influential than previously thought. According to Nurul Yaqin, chairman of the Indonesian Islamic History Community Association, Ibrahim might be identified with "Shi Jin Qing" mentioned in Ming Dynasty records—a high-ranking commander authorized by three powers (Pasai Kingdom, Javanese kingdoms, and Ming China) to secure the crucial spice route from Sumatra to Gresik.

This wasn't just religious work—it was strategic geopolitical positioning. The construction of Gresik Port in 1425 represented a major joint investment that transformed the town into Java's largest Islamic port within a century.

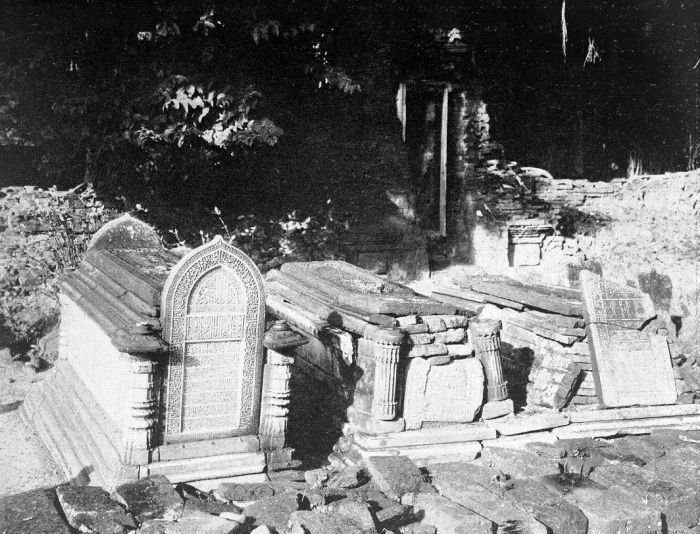

Evidence from tombstone analysis suggests Ibrahim may have been Sultan Zainal Abidin of Pasai, father of Malikah Nahrasyiyah—making his influence extend from Central Asia to the powerful Pasai Sultanate and beyond.

How His Influence Still Shapes Indonesian Islam

Ibrahim Asmarakandi died in 1419 and was buried in Gresik, where his grave attracts over 1.5 million pilgrims annually. But his real legacy isn't just a tomb—it's the entire framework of Indonesian Islam.

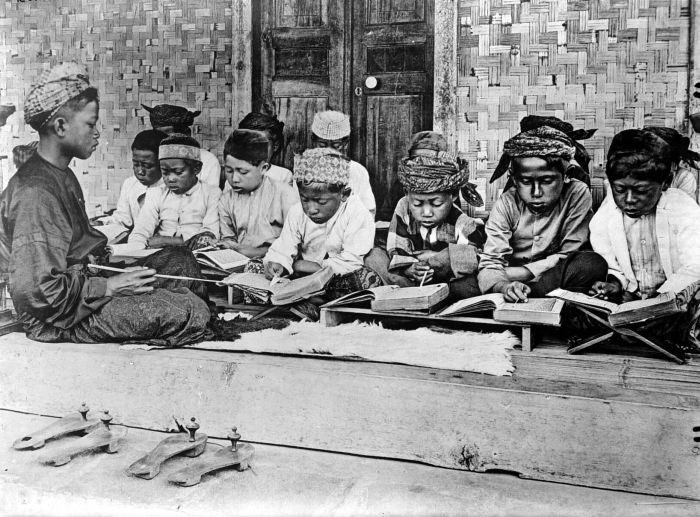

The pesantren (Islamic boarding school) system he pioneered now comprises over 28,000 institutions serving millions of students. His moderate, culturally-adaptive approach helped shape Indonesian Islam's characteristically tolerant character. Through his sons and grandsons—including Sunan Ampel, Sunan Giri, Sunan Bonang, and Sunan Drajat—his influence spread throughout Java and beyond.

According to 2025 research by Dr. M. Imam Sibli and colleagues published in QOMARUNA Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Sunan Gresik's educational methodology of integrating Islamic teachings with local wisdom remains relevant for contemporary Islamic education in Indonesia.

What This Story Changes About Islamic History in Southeast Asia

Ibrahim Asmarakandi's story fundamentally challenges how we understand Islamic expansion in Southeast Asia. His journey proves that Islam's spread to Indonesia wasn't simply about Arabian or Indian influence—it was a complex network involving multiple Islamic civilization centers, including the often-overlooked scholarly powerhouses of Central Asia.

The Silk Road didn't just carry goods—it carried ideas, scholars, and spiritual teachers who would transform distant lands. From Samarkand's magnificent madrasahs to Java's coastal mosques, Ibrahim created connections that lasted centuries, reminding us that medieval Islamic civilization was truly global, with knowledge flowing across vast distances through networks of dedicated individuals.

Today, when millions of Indonesians practice a moderate, culturally-rooted Islam that respects diversity while maintaining core principles, they're living Ibrahim Asmarakandi's vision—a Central Asian scholar's gift to Southeast Asia that continues shaping lives six centuries later.

Sources:

Dr. Zumrotul Mukaffa (UIN Sunan Ampel), Nurul Yaqin (MAPSINU), Dr. M. Imam Sibli et al. (2025), Michael Laffan, historical documents including Babad Tanah Jawi, and archaeological evidence.