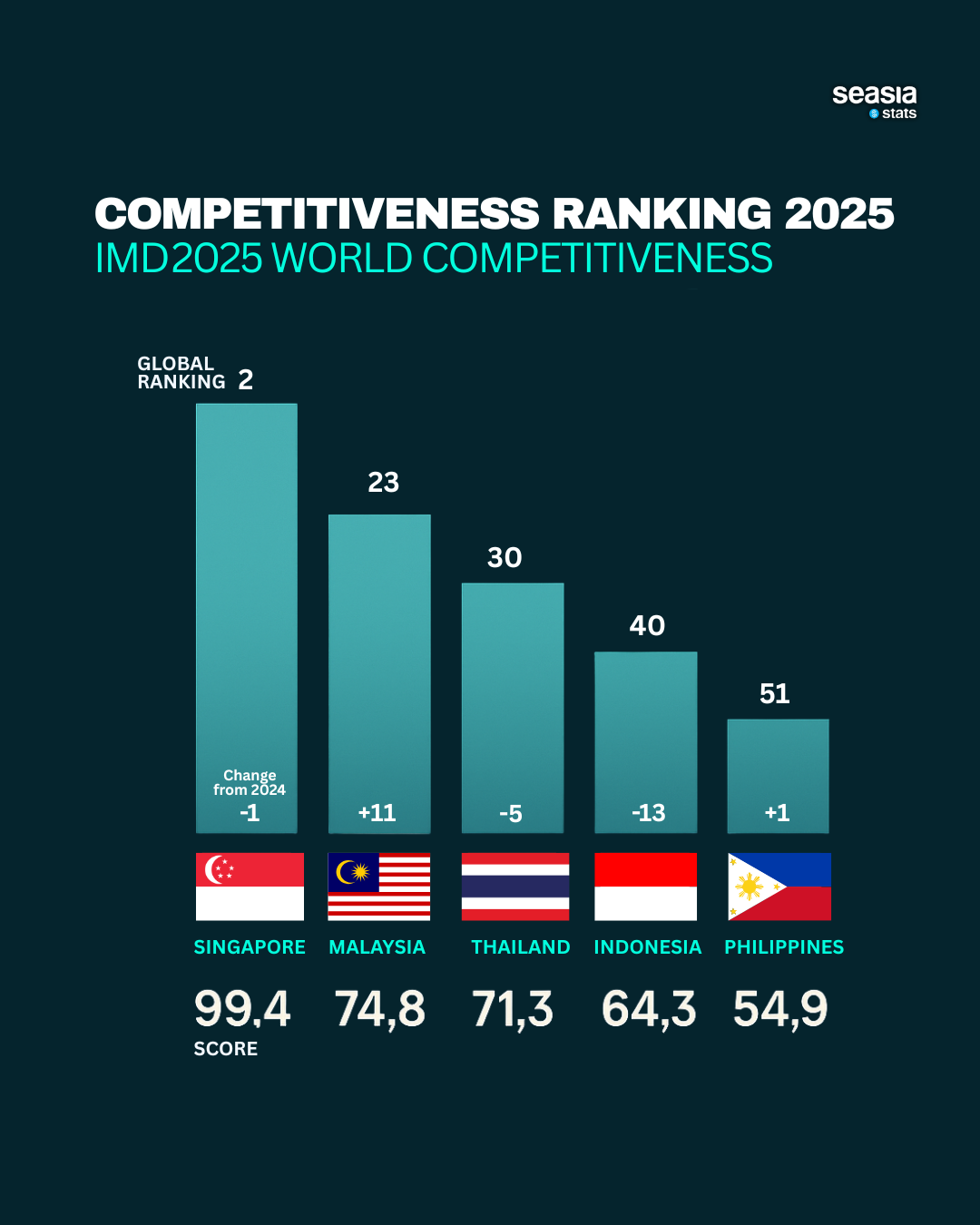

The newly released IMD World Competitiveness Ranking 2025 provides a telling snapshot of economic momentum and disparity across Southeast Asia. Singapore once again asserts its position as the region’s top performer, holding firmly at 2nd place globally, slipping just one rank from last year. But the biggest surprise comes from Malaysia, which catapulted 11 spots upward to 23rd place, signaling a resurgence of reform-driven momentum. In contrast, Indonesia takes a sharp hit, falling 13 positions, marking one of the steepest drops in the region. Thailand slipped by five places to 30th, while the Philippines edged up slightly, rising one position to 51st.

Unlike rankings that rely solely on GDP or productivity, the IMD World Competitiveness Center defines competitiveness as a country’s ability to generate sustainable prosperity for its people. It’s a complex interplay of economic performance, infrastructure, business environment, and—critically—government efficiency. The 2025 rankings reflect both statistical data (or "hard data") and executive perceptions gathered from over 6,000 senior business leaders worldwide.

Singapore, despite a marginal drop, remains a global titan. Its score of 99.4 reflects world-class infrastructure, top-tier education, digital governance, and policy agility that few can rival. What makes Singapore stand out is not just its economic strength, but its ability to anticipate future challenges—whether in sustainability, cybersecurity, or shifting global trade.

But the real headline this year is Malaysia’s dramatic climb. From 34th in 2024 to 23rd in 2025, Malaysia’s jump represents one of the largest positive moves among all 69 countries ranked. This improvement reflects significant strides in digital governance, foreign investment policy, and infrastructure upgrades. It also indicates improved business confidence, driven by efforts to reduce bureaucratic red tape and expand regional economic zones.

Meanwhile, Thailand and Indonesia both face headwinds. Thailand’s 5-point slip reflects lingering concerns around innovation stagnation, policy predictability, and demographic pressures. Indonesia, however, fell a staggering 13 ranks to 40th—a sharp warning sign. The decline suggests rising worries over regulatory unpredictability, bottlenecks in infrastructure delivery, and governance inefficiency. Despite the country’s large market and bold visions—like the relocation of its capital to Nusantara—the lack of consistent execution appears to be weighing down investor confidence.

The Philippines, while still in the lower half of ASEAN, rose by one position to 51st. That small bump hints at a recovery in perception following pandemic-era volatility. The country continues to rely on its young, tech-savvy population and a vibrant BPO sector. However, long-term competitiveness will depend on education reform, infrastructure investment, and stronger policy coordination.

The IMD methodology blends 170 statistical indicators and 92 survey-based criteria, structured across four equally weighted pillars: economic performance, government efficiency, business efficiency, and infrastructure. Using a standardized deviation scoring system, IMD ensures consistency across economies of varying size and structure.

What this year’s results underscore is that reform, adaptability, and good governance are now the defining traits of competitiveness. Malaysia’s leap proves that progress is possible with focused policymaking. Singapore remains the model of long-term vision and execution. Meanwhile, Indonesia and Thailand must take these results seriously and prioritize structural reforms, regulatory clarity, and infrastructure delivery. The Philippines, though still trailing, may be entering a more promising phase—if it seizes the momentum.

In an increasingly volatile global economy shaped by realigned trade flows, digital transitions, and geopolitical flux, ASEAN’s ability to turn potential into policy and resilience into results will determine its true future standing on the world stage.