Ancient Egyptian civilization is known as one of the longest-lasting in human history, spanning from around 3100 BCE to 30 BCE, when the region eventually came under Roman rule. Because of its remarkable longevity, it is not surprising that at some point, the ancient Egyptians themselves began studying and preserving relics from even earlier periods.

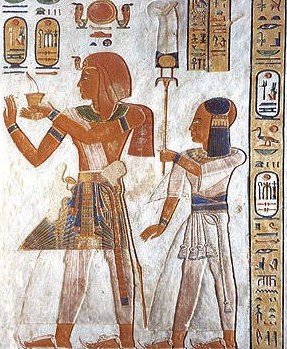

One prominent figure known for his interest in ancient monuments was Prince Khaemwaset, the fourth son of Pharaoh Ramesses II of the 19th Dynasty. He lived about 3,300 years ago, during the 13th century BCE (c. 1281–1225 BCE).

Khaemwaset is often referred to as “the first archaeologist in history” for his role in identifying, restoring, and documenting ancient monuments built by earlier dynasties.

A Fascination with the Past

Khaemwaset lived during the reign of Ramesses II (c. 1279–1213 BCE). He served as High Priest of Ptah in Memphis, one of the most prestigious religious positions in ancient Egypt. As High Priest, he was responsible for conducting religious rituals, maintaining temples, and upholding spiritual traditions.

However, archaeological evidence and historical records reveal that Khaemwaset had a deep personal interest in monuments from the Old and Middle Kingdoms.

He visited, studied, and repaired numerous ancient structures that had deteriorated over time. In several sites, he added new inscriptions to re-identify the names of the kings or builders associated with the original monuments.

Khaemwaset’s Act of Royal Preservation

One of Khaemwaset’s most documented acts was the relocation of the statue of Kawab, the son of King Khufu (builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza). The damaged statue was moved to the Temple of Ptah in Memphis, where Khaemwaset added an inscription explaining its original ownership.

In addition, several small statues of earlier kings, including Khufu and Pepi I, were discovered in a chapel built by Khaemwaset in Saqqara, reflecting his strong reverence for Egypt’s royal ancestors.

Religious Activities at the Serapeum

As High Priest of Ptah, Khaemwaset was also closely involved in the administration of the Serapeum at Saqqara, the burial complex for the sacred Apis bulls, which were considered manifestations of the god Ptah. He is believed to have expanded the complex and overseen the construction of new underground galleries for Apis burials.

When the Serapeum was rediscovered by archaeologists in the 19th century, more than fifty shabti figurines bearing Khaemwaset’s name were found at the site. However, this does not indicate that he was buried there.

These figures were likely religious votive offerings placed in honor of his significant role in the complex’s religious activities.

Khaemwaset and the Deification of Imhotep

Beyond restoration projects, Khaemwaset is also noted for his involvement in other religious contexts. One of the most important artifacts linked to him is a libation vessel dedicated to Imhotep, the legendary figure from the time of King Djoser.

On this vessel, Imhotep is referred to for the first time as the “son of Ptah,” a title that later became the foundation for his deification as the god of wisdom and healing in later periods. This marked an important step in the development of the Imhotep cult, which flourished in the centuries that followed.

Inscriptions on the Pyramid of Unas

One of Khaemwaset’s most significant legacies is a large inscription carved on the southern side of the Pyramid of Unas in Saqqara. The text contains his name and titles, indicating his involvement in the monument’s maintenance and restoration.

This inscription is a clear example of how high officials during the Ramesside period inscribed their names on older monuments—not to claim them, but to honor and preserve the memory of earlier kings.

In modern scholarship, this act is often seen as one of the earliest forms of historical documentation, functioning much like an ancient identification label that reflects a conscious awareness of the value of cultural heritage.

The Enduring Memory of the Prince

Centuries after his death, Khaemwaset’s name continued to be remembered. He appears as the main character in an ancient Egyptian literary work titled Setne Khamwas, which portrays him as a prince fascinated by tombs and the relics of the past.

In these stories, he is depicted wandering through royal and scribal tombs, reading inscriptions on their walls, and studying the history of those who came before him.

Although the Setne tales were written long after his lifetime and contain mythological elements, the protagonist is clearly based on the historical Khaemwaset, renowned for his deep interest in Egypt’s past and its ancient knowledge. His portrayal in this literature shows that his reputation as a “lover of history” endured well into the Ptolemaic era, centuries after his death.

Reference:

https://www.mdpi.com/2571-9408/5/3/115#:~:text=The%20figure%20of%20Khaemwaset%2C%20the,monuments%20%5B1%2C2%5D.