Ancient Egypt lasted for around three thousand years as a unified, remarkably stable civilization.

One of the reasons its monuments, writings, and culture have survived so well is that even in antiquity the Egyptians had people whose duties resembled those of modern archaeologists.

They took care of old monuments, restored decayed buildings, cleared away debris and sand, recorded inscriptions, and preserved memories of their long past.

Below are several perspectives on how this came about, and who among the ancient Egyptians played especially prominent roles.

How Does a Long-Lasting Civilization Lead to Antiquarian Activity?

When a civilization endures for thousands of years, many monuments built in early phases become ancient relics to later generations. Over centuries, things deteriorate, structures are buried in sand or rubble, inscriptions fade, and original purposes are forgotten.

For Ancient Egypt this happened repeatedly: tablets, pyramids, statues from the Old Kingdom, for example, became old even for those in the New Kingdom.

Because the Egyptian belief system placed strong importance on memory, the continuity of political legitimacy, divine kingship, and funerary cults, preserving the past was not merely aesthetic, it was religious and political.

Temples maintained “houses of life” (Per‑Ankh) with archives and libraries, priests copied and preserved texts, and kings sometimes commissioned restorations or made records of earlier monuments.

Thus the idea that something “ancient” had value was built into the structure of Egyptian society.

Early Examples of “Archeology” Practice

Even by the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE), there is evidence of pharaohs undertaking projects to excavate, restore, or clear ancient monuments.

A famous example is Thutmose IV, who, according to Encyclopedia Britannica, as a prince cleared away the sand that had accumulated around the Great Sphinx.

He later erected a stela (known as the Dream Stela) between the paws of the Sphinx, which records the act and its religious significance.

Another earlier tradition involved priestly and royal officials keeping genealogies, keeping records of deeds, and preserving the names of past kings, even when parts of monuments had been destroyed.

Khaemweset: The First Known “Egyptologist”

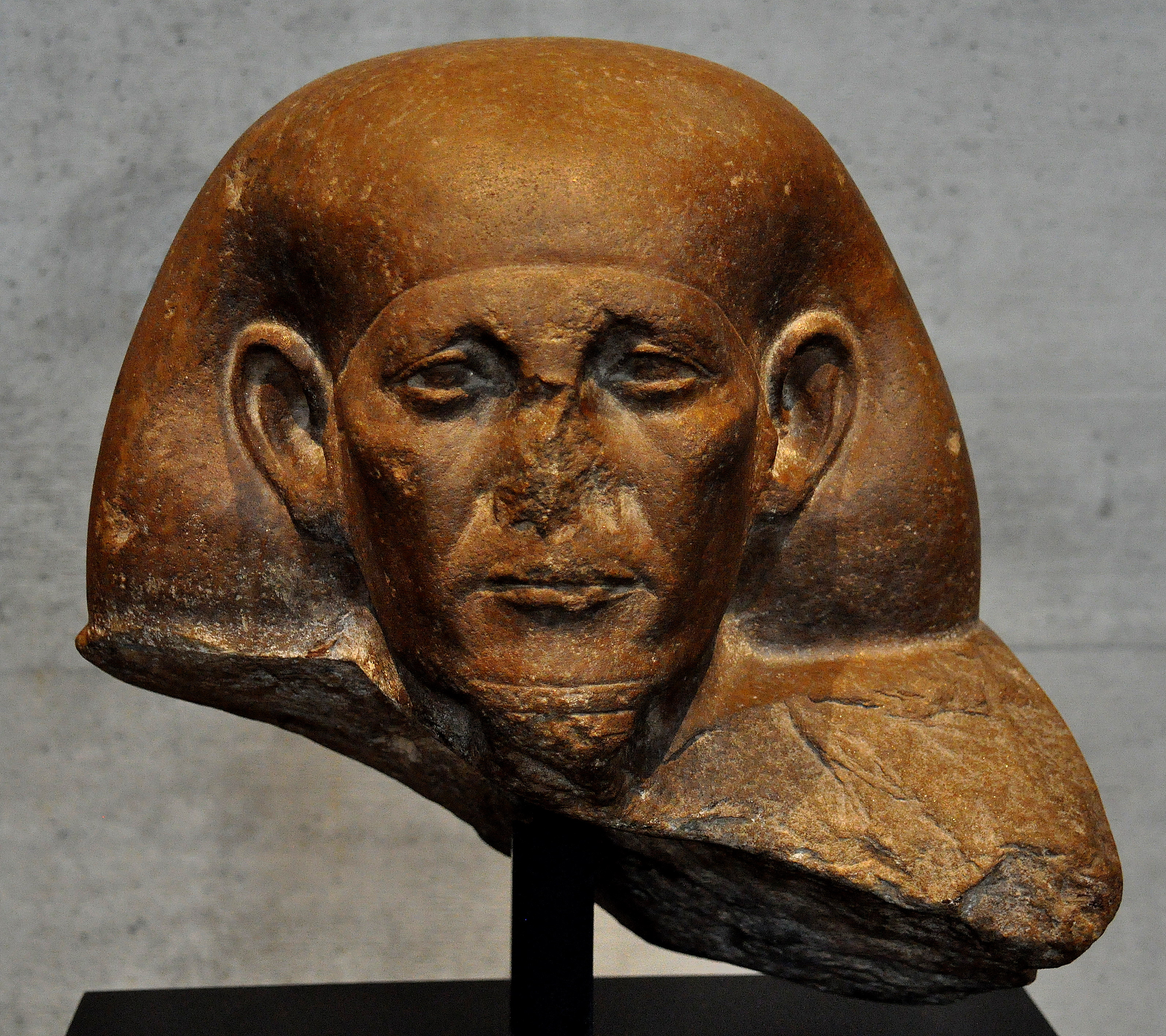

Perhaps the most famous ancient Egyptian who performed work akin to modern archaeology is Khaemweset, a son of Ramesses II (reign c. 1279–1213 BCE). He is often called the first Egyptologist, according to Ancient Origins and World History Encyclopedia.

As High Priest of Ptah in Memphis, Khaemweset used temple records to identify old monuments decrepit with time.

He restored many of them, from Saqqara to Giza. Among those he worked on were the pyramid of Unas, the mastaba of Shepseskaf, the pyramids of Sahure, Djoser, and Userkaf.

He also restored or retrieved elements such as statues, re‑inscribing names of the original builders, as well as noting his own restorations.

He cared enough not only to perform restoration but to document who built originally, and to renew funerary cults associated with older kings.

Therefore, while the term “archaeologist” is modern, his role was very similar: identifying ancient remains, restoring them, recording inscriptions, and ensuring memory of earlier generations.

Other Notable Figures

Besides Khaemweset and Thutmose IV, there were other individuals who engaged in actions preserving Egypt’s past.

Manetho, a priest during the Ptolemaic period (3rd century BCE), wrote Aegyptiaca, a history of Egypt in Greek, chronicling rulers from the mythical to the historical.

Though he did not physically restore monuments, his work preserved knowledge of the past and helped later scholars reconstruct Egyptian chronology.

Mentuemhat, a Theban high priest and mayor during the late period (around 700 BCE), is known for having many statues of himself, but also for choosing archaizing, that is, using older styles and preserving or emulating art and religious forms of earlier periods.

While he is less directly involved in restoration, this kind of antiquarian taste and respect for earlier forms is part of the same impulse to value and preserve the past.

It Wasn’t Exactly Like Archeology We Know Today

Although many individuals displayed behaviors and carried out deeds similar to those of modern archaeologists, Ancient Egypt did not have a fully formed profession exactly like ours (with methods of stratigraphy, dating, fieldwork, etc.).

Most of the restoration work was carried out by priests, artisans, or members of the royal family. The motivations were often religious or political rather than purely scientific: restoring cults of past kings, affirming legitimacy, or demonstrating piety.

Ancient craftsmen and priests had records (temple archives) and skills (inscription, masonry, stone working) that supported those restorations. But the modern systematic archaeology with its scientific tools is a much later development.