Among the world’s great literary masterpieces, such as India’s Mahabharata and Ramayana or the Greek epics of Homer, the Indonesian archipelago also boasts an equally magnificent creation: La Galigo, the world’s largest epic from the Bugis people of South Sulawesi.

Recognized by UNESCO in 2011 as part of its Memory of the World register, La Galigo spans more than 6,000 folio pages, or roughly 300,000 lines of verse, earning it the title of the longest literary work ever written by humankind.

Despite its monumental status, La Galigo remains relatively underappreciated in its own homeland. Among some Bugis communities, particularly followers of the indigenous Tolotang belief system, the text holds a sacred position comparable to that of a holy scripture. They regard La Galigo not merely as a mythological tale but as a spiritual truth passed down from their ancestors.

The Sacred Heart of Bugis Culture

Also known as Sureq Galigo, the epic is a vast collection of poetic verses narrating the myth of the world’s creation and the origin of humanity in pre-Islamic Bugis culture. Beyond its immense literary value, it reflects deep spiritual, moral, and cosmological insights of the ancient Bugis worldview.

In Tolotang tradition, reciting La Galigo is not an ordinary activity. The reading is preceded by sacred rituals, such as burning incense, offering food, and sacrificing a chicken or goat.

The act of recitation is regarded as a form of prayer, believed to bring blessings, ward off misfortune, and even heal illness. For the Tolotang community, every passage of the text carries divine and mystical power.

From Oral Tales to Lontara Script

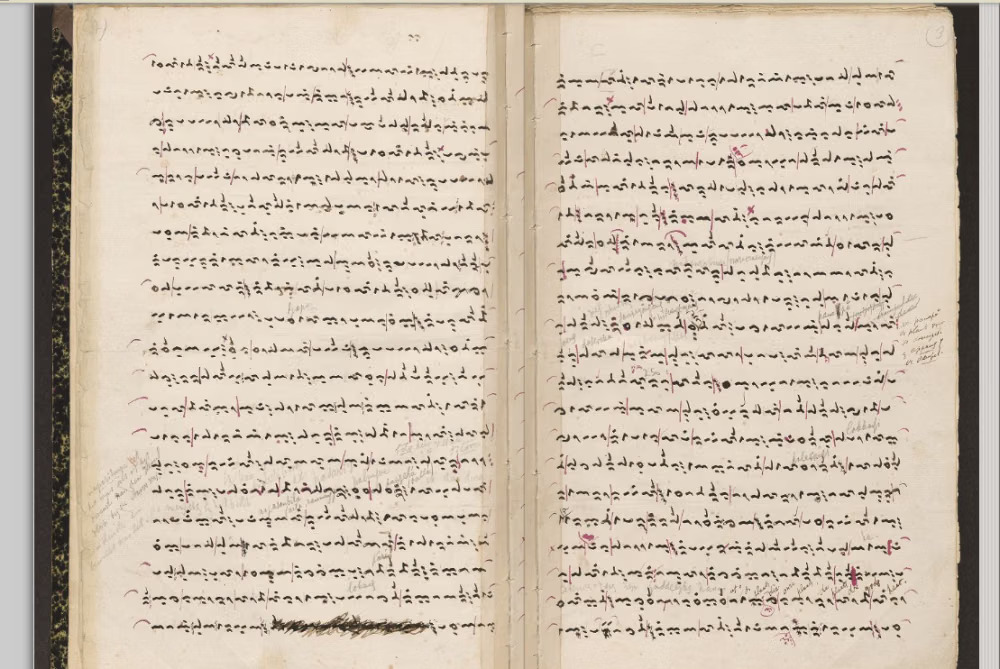

La Galigo was originally part of an oral tradition, passed down through generations by storytellers and traditional priests. It was only in the first half of the 19th century that the epic began to be transcribed using Lontara script, the distinctive Bugis writing system believed to have descended from South India’s Pallava script.

The text is written in five-syllable verse with strict structure and refined poetic aesthetics. Interestingly, La Galigo was never meant to be merely read, it was sung or chanted.

In the Bugis language, this tradition is known as laoang or selleang, typically performed during customary and spiritual ceremonies. In some Bugis regions, this singing tradition is called massureq or maggaligo, and it continues to be practiced today in areas such as Pangkajene, Wajo, Soppeng, Luwu, and Sidenreng Rappang.

Sawérigading: The Central Character

Narratively, La Galigo tells the story of Sawérigading, the grandson of Batara Guru, the first human to descend from the heavens and become king of Luwu, a kingdom located in the northern region of Bone Bay. After Batara Guru descended to earth, he was succeeded by his son, La Tiuleng or Batara Lattu’, who had twin children: Sawérigading and Wé Tenriabéng.

The twins were raised separately, but when they reached adulthood, they met again, and Sawérigading fell in love with his own twin sister. This forbidden love was rejected, as it was believed to bring great disaster.

To forget his feelings, Sawérigading set out on a long journey to distant lands. He eventually arrived in China, where he married a princess named Wé Cudaiq, whose face resembled that of his sister. From this marriage, a son was born—La Galigo, who would later become the ruler of the middle world (earth).

When Sawérigading returned to Luwu, his ship sank. He and his wife were then believed to have become rulers of the underworld, while Wé Tenriabéng ascended to the upper world with the gods.

This story reflects the Bugis cosmological view of a three-layered universe: the upper world (boting langi’), the middle world (ale kawa’), and the underworld (uri’ liu).

Structure, Values, and Distribution

La Galigo consists of dozens of episodes, or tereng, each following a strict structural and literary framework. Every part contains moral teachings, social principles, genealogies of deities, and life philosophies that shape the Bugis worldview.

This epic is not only known in South Sulawesi but has also been found in various versions and fragments across other regions, such as Central Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi, Gorontalo, and even the Malay Peninsula, including Kelantan and Terengganu.

Manuscripts of La Galigo are now preserved in major libraries around the world, including in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States, evidence of the Bugis cultural influence that transcends geographical boundaries.

Interaction with Islam and Modern Adaptation

With the arrival of Islam in South Sulawesi, La Galigo underwent an intertextual transformation.

In the version Bottinna I La Déwata Sibawa Wé Attaweq, Islamic elements such as Arabic prayers, quotations from the Qur’an, and references to the Asmaul Husna (the 99 Names of God) appear. Interestingly, these Islamic influences did not erase pre-Islamic beliefs; instead, they coexist harmoniously within the text.

La Galigo reached international acclaim when American avant-garde director Robert Wilson adapted it for the global stage in 2004. The performance premiered in Singapore and was later staged in major European cities including Amsterdam, Barcelona, Madrid, Lyon, and Ravenna, before continuing to New York.

After touring the world, La Galigo finally returned home to Indonesia in 2011 with a performance in Makassar, the same year UNESCO inscribed it into the Memory of the World Register as part of the world’s documentary heritage.

Preservation and Challenges

Despite its global recognition, preserving La Galigo faces serious challenges. The declining ability of local communities to read Lontara script and the fading understanding of Old Bugis language pose major threats to the survival of this cultural treasure.

In the past, the responsibility for safeguarding La Galigo manuscripts and traditions largely rested on the Bissu, Bugis priests who also served as spiritual guardians. However, in modern society, the Bissu’s social position has often been marginalized due to their complex gender identity and religious roles. As their influence weakened, their function as keepers of the tradition also diminished, leaving the La Galigo legacy increasingly vulnerable to oblivion.

Now, after being recognized as a world heritage by UNESCO, the preservation of La Galigo is no longer solely the duty of the Bugis people but a collective responsibility of the entire Indonesian nation. It stands not only as a cultural treasure of South Sulawesi but also as a symbol of Indonesia’s civilizational pride and a monumental contribution to world literature.