Imagine a sea voyage without modern maps, without engines, and without any guarantee of reaching land. Around 3,500 years ago, a group of ancient seafarers succeeded in crossing the Pacific Ocean, sailing some 2,300 kilometers from the Philippines to Guam in the Mariana Islands.

A recent archaeological study published in Science Advances reveals the earliest evidence of rice in the Pacific Islands. This discovery not only resolves a question that has intrigued researchers for decades, but also sheds light on early human migration and the cultural meanings carried across vast oceans.

Small Evidence That Reshapes a Larger Narrative

This significant finding comes from Ritidian Beach Cave, a coastal cave at the northern tip of Guam. It was here that researchers discovered microscopic traces of rice adhering to the surfaces of ancient pottery.

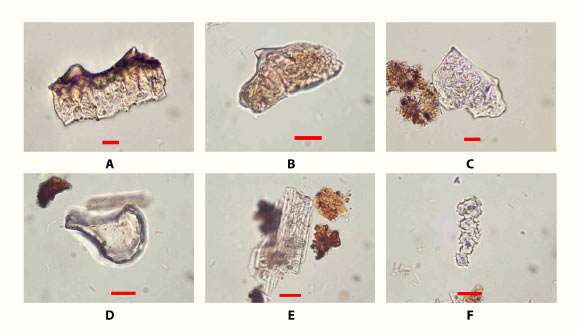

Rather than intact grains or agricultural fields, the evidence consists of phytoliths, microscopic silica structures formed within plant cells that can survive for thousands of years after the plant itself has decayed.

Through detailed analysis, archaeologists confirmed that the shapes of the phytoliths matched those found in rice husks, leaves, and floral parts. Notably, these rice traces were found only on pottery surfaces and on a single stone tool, and were entirely absent from the surrounding soil sediments.

This sharp contrast strongly indicates that the rice was not the result of natural contamination or later intrusion, but was deliberately handled and used by humans at the time.

High-resolution X-ray scanning and thin-section analysis of the pottery further showed that rice husks were not mixed into the clay as tempering material. In other words, rice was not used in the pottery-making process itself, but interacted with finished vessels—most likely during food preparation, serving, or ritual activities.

Rice in an Environment Unsuitable for Rice Cultivation

The discovery becomes even more compelling when viewed in the broader Pacific context. To this day, Pacific Island communities have traditionally relied on food sources such as breadfruit, taro, yams, bananas, and coconuts.

Rice is notoriously difficult to cultivate on many Pacific islands due to thin limestone soils, steep topography, and unpredictable rainfall patterns.

Historical accounts from the 16th to early 17th centuries note that the Chamorro people of the Marianas cultivated and consumed rice only in very limited quantities.

Rice was reserved for special occasions, such as ceremonial events or moments when someone was near death. Rice consumption increased significantly only after the period of intensive Spanish colonial rule.

For this reason, the presence of rice from the earliest phases of settlement in Guam suggests that it was far more than an emergency food source. Rice was something valued enough to be carried across open seas and used with great care and intention.

Sacred Caves and Traces of Ritual

The location where the rice was discovered also carries strong symbolic meaning. Ritidian Beach Cave lies within an area long recognized as a ritual landscape, surrounded by other caves, burial sites, ancient carvings, and ornamental remains.

In Chamorro tradition, caves are regarded as sacred spaces for communicating with ancestral spirits and conducting important spiritual practices.

Notably, only one section of the Ritidian cave complex shows a strong presence of rice remains. Other sites from the same period, both open coastal camps and nearby caves, show little to no evidence of this plant.

This pattern strengthens the interpretation that rice was used in a specific ceremonial context rather than for everyday consumption.

A Planned Voyage, Not an Accident

For nearly two decades, scholars have debated whether the first inhabitants of the Mariana Islands arrived by accident—carried by currents and winds—or through carefully planned seafaring voyages. The rice evidence represents a crucial piece of this puzzle.

Transporting rice means carrying something fragile, culturally valuable, and not easily replaced. This strongly suggests that the journey was undertaken with deliberate planning.

These early Austronesian seafarers relied not only on navigational skill, but also on a clear cultural vision: bringing their identity with them to new lands.

Previous ancient DNA analyses of human remains from Guam have shown that the earliest settlers originated from central or northern Philippines, with deeper ancestral roots in Taiwan.

This migration route aligns with the broader expansion of Austronesian-speaking populations, which today encompass nearly 400 million people, stretching from Madagascar to Easter Island.